︎︎︎ Full Report (PDF)

1. Executive Summary

2. Introduction

3. Research Design

4. The State of Non-Punitive School Discipline Efforts in CA

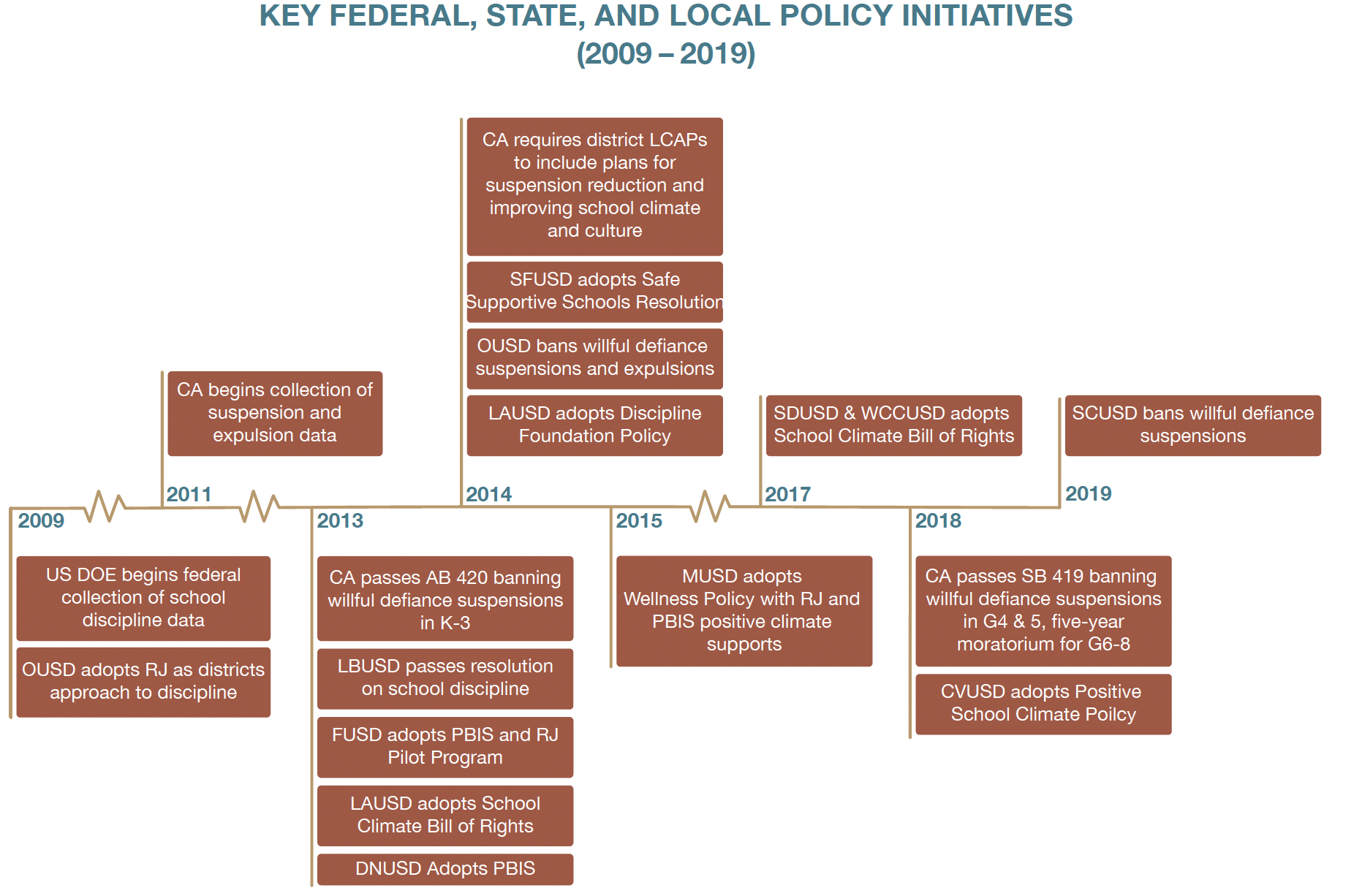

a) Federal, state, and local policies have changed

b) Schools plotted on the school climate and culture quadrants

c) Punishment and exclusion co-existed with alternative approaches

d) Racial disproportionality persisted such that punitive discipline remains more prevalent for Black, Indigenous, and gang-labeled Latinx students

5. Supportive Strategies and Remaining Obstacles

a) Program and approach adoption

b) Organizational structures

c) Relationships

d) Identity, ideology, and deep-

seated beliefs

e) Larger social contexts

6. The Role of Core Funders

a) Funding the translation of interest convergence into state and local policy

b) Facilitating the creation of a dominant policy frame

c) Spotlighting restorative justice as alternatives to punishment and exclusion

d) Contributing to the expansion of the restorative justice market

e) Impact of local organizing pressures differed regionally

7. Conclusion

8. Appendices

9. Our team

10. In loving memory

11. Endnotes

Digital Library

Our findings review the impact of efforts to reform school discipline policy and practice including the role of alternatives to punishment, including restorative justice and PBIS. In addition, our findings offer insight on how school, district, and regional-level supports and constraints shaped discipline policy and practice in schools.

Read the report below.

Transforming School Discipline in California

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

School climate, culture, and safety are a perennial concern for all stakeholders in schools — including parents, students, teachers, counselors and school leaders. These inter-related school conditions influence whether students want to attend school, how focused they can be on learning, teachers’ ability to teach, teachers’ excitement and pride in their craft, and leadership retention.

As many educators point out, school climate, culture, and safety is the water that school communities swim in — and can run the gamut from invigorating to toxic. Disciplinary approaches and systems are often the most visible and identifiable tools school leaders and educators use to shape and navigate these waters.

These disciplinary approaches and systems impact academic and social outcomes1. More importantly, they teach young people what to expect from society and their place in it.

In many classrooms and communities students continue to be told that education is the great equalizer and that if they stay seated, do their work, raise their hands to speak, follow directions quickly, and remain well-behaved, they will land a good job and enjoy a good life.

The American Dream, accepted and venerated as truth, is that education provides the opportunity for everyone to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. However, this truth fails to extend to the vast majority of Black, Indigenous, Latinx and other youth circumscribed to poverty. Despite entering school with high hopes for education, research shows that positive connection to, and perception of, school decline over time — and this decline is more pronounced for lower-income students and students of color.2

Students who question the school-to-low-wage-labor or -nothing pipeline, act out or opt out. Schools — resource strapped and unequipped — often resort to suspension, expulsion, deficit narratives, and increased partnerships with law enforcement.

Beyond Suspension Decline shares the findings from the largest qualitative study of school climate and discipline in the state of California and provides an analysis of recent efforts to challenge punitive and exclusionary school discipline. Findings summarize four years of case study data across 34 schools in 17 California districts that span urban, suburban, and rural schools from the Oregon to Mexico borders.3

What we know is there is no quick fix to overly punitive and exclusionary school systems. And there is no quick fix to repair the harm Black, Indigenous, and Latinx youth experience in California school systems. To improve schools we must better understand the root problem, identify the institutional supports and obstacles educators and communities encounter as they attempt to create change, and recognize the individual strategies and practices that are promising.

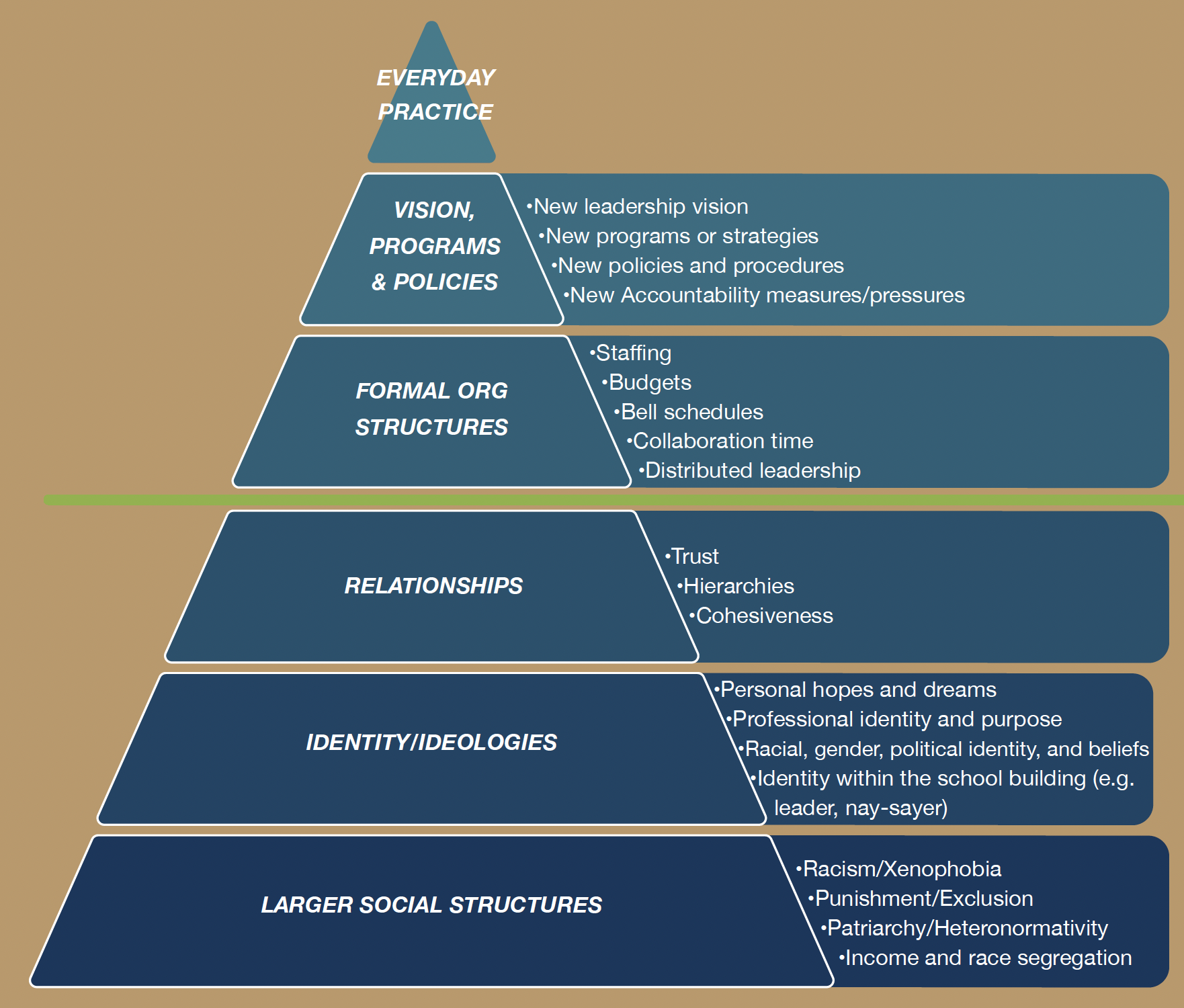

Our research finds that the incorrect framing or understanding of the problem; construction of solutions without acknowledgment of the pre-existing institutional footholds or barriers; or the lack of a vision and models of better alternatives lead efforts astray and leave educators and organizers burned out.

We hope Beyond Suspension Decline impresses upon readers the complexity of “changing the water” of school climate, culture, and discipline in schools. We hope this report also contributes to the ongoing analysis, reflection, and re-imagination of schools.

The Study

After a decade or more of awareness building, community organizing, activism, and school discipline policy reform,5 statewide school discipline data show mixed and sometimes confusing results. California schools achieved a reduction of school suspensions, particularly between 2011 and 2015, when the average rate fell from 5.8% to 3.8%.

However, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students continue to be disproportionately suspended and expelled, and for subjective reasons.6 Moreover, violence, victimization, bullying, and harassment in middle schools improved over this period, and yet the percentage of students who experienced caring relationships with adults, high expectations from teachers, opportunities for meaningful participation, and positive perceptions of school safety declined.7

Our interdisciplinary research team of diverse educators, researchers, and lawyers interviewed 553 administrators, teachers, staff, parents, students and community-based organization leaders. We observed 291 classrooms over 191 researcher-days and shadowed a diverse spectrum of students with varying degrees of interactions with school discipline systems. We expanded our observations beyond instructional time to staff meetings, school activities, school suspension rooms, community centers, and restorative justice spaces.

We Sought to Answer:

| 1. How have school disciplinary cultures (i.e., narratives, norms, and practices) changed in California? |

2. What strategies and conditions support efforts to move away from punitive or exclusionary school discipline practices? What obstacles remain? |

3. What role has an ecosystem of community-based and advocacy organizations in California, and a core funder, The California Endowment, played in these efforts? |

The extensive interviews and observations often produced more questions and required critical thought about how to organize such a large amount of data for our readers.

Summary of Findings

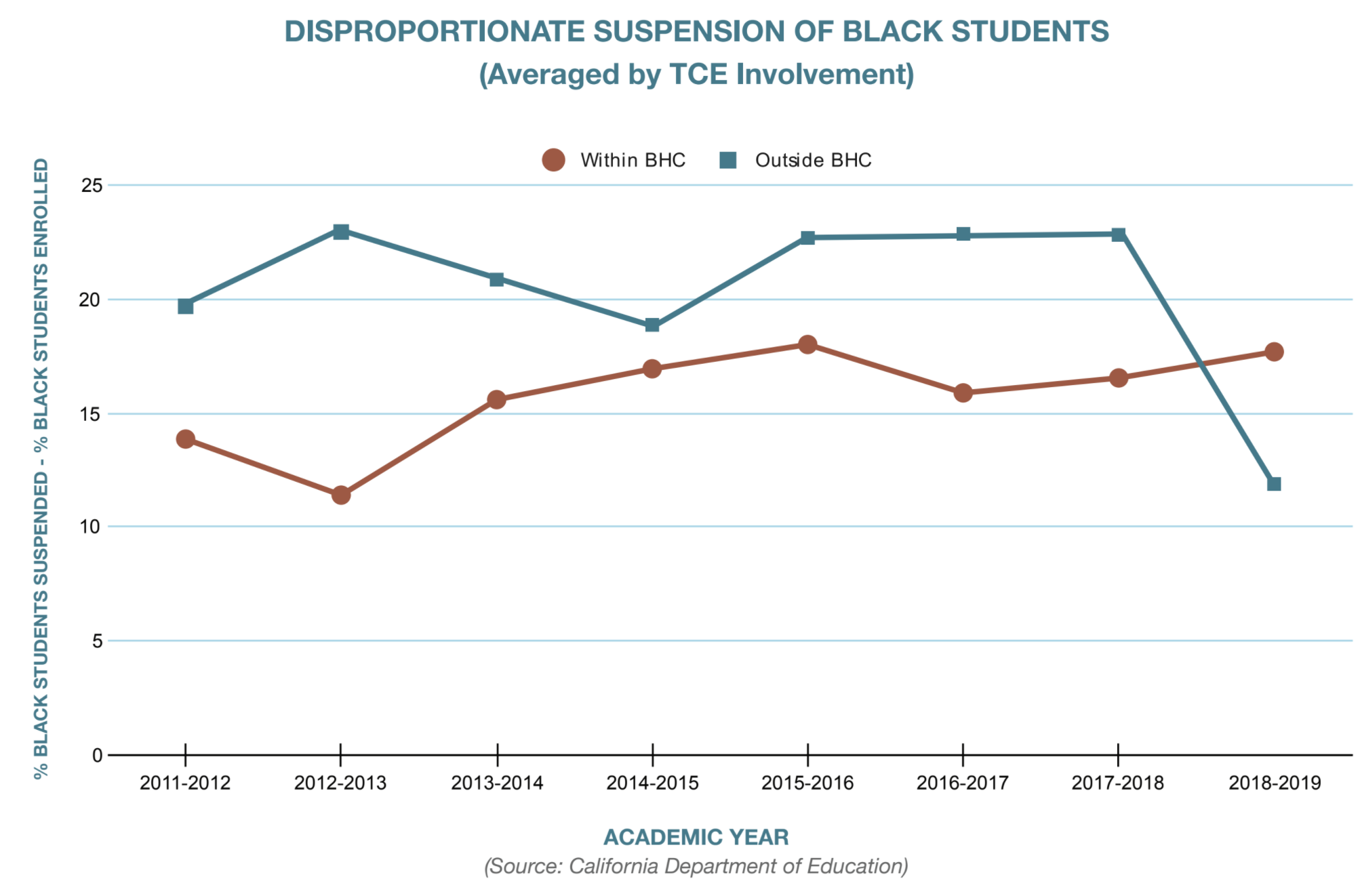

- School and district leaders share a common narrative that zero-tolerance policies do not work and school suspensions are not useful for improving student behavior or learning. While rightfully celebrated as a win, we found that administrators rarely cite the disproportionate impact of suspensions and expulsions on students of color as central to their efforts to shift disciplinary practices. This may partially explain the scarcity of race conscious solutions and the persistent racial discipline gap.

-

School climate, culture, and discipline improve the most in schools that experience or pursue changes to deeper organizational structures first. We found this to be true of schools with a decline in overall enrollment and in schools that intentionally create smaller learning communities, increase teacher collaboration time, dismantle punitive dean of students positions and in-school suspension rooms, expand student leadership and organizing opportunities, and offer robust social and emotional supports. Otherwise, add-on programs, like a restorative justice coordinator position with little power, become afterthoughts, and schools regressed quickly back to punishment when funding for these programs ceased.

-

For successful school transformation, school leaders must hold capacity-oriented perspectives of both adults and students. School leaders who hold capacity-oriented perspectives of both adults and students encourage teacher leadership, foster respectful and professionally engaging adult communities, make time for staff collaboration, and support adults to support youth leadership and activities.

-

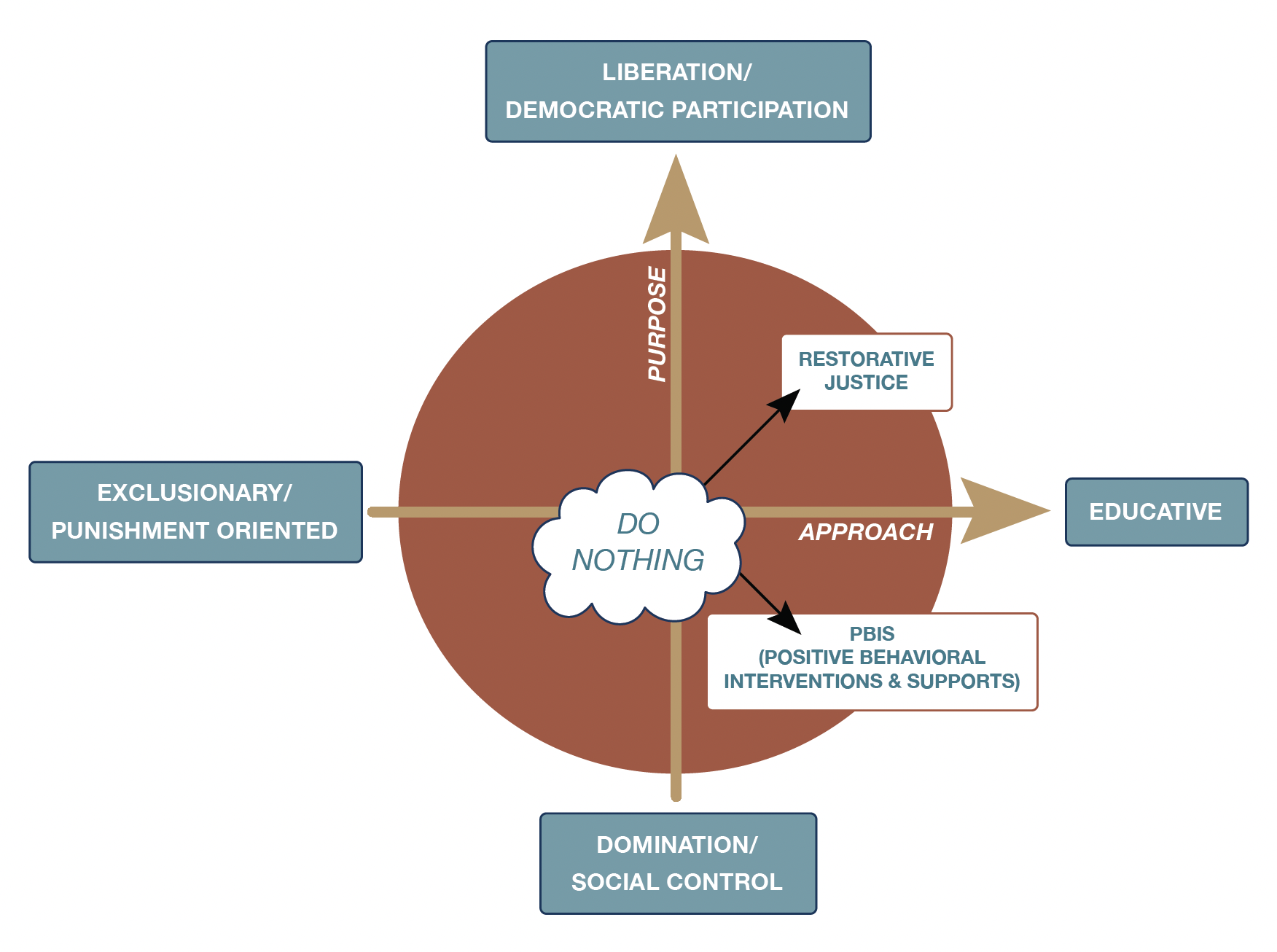

Despite reducing suspensions and expulsions, punitive and exclusionary attitudes and practices co-exist with positive and supportive practices like restorative justice (RJ) and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in most schools. Schools without articulated alternative discipline approaches tend to default to punitive, exclusionary, and social control orientations to discipline.

-

School police remain a steady presence in schools. While educators widely accept police as necessary, only a minority of teachers have actual interactions with school police. Simultaneously, escalation, criminalization, aggression, and violence characterize police interactions when they do occur. Reports of police escalating violence in schools occurred more often in schools that serve Black and Indigenous youth.

-

School disciplinary systems continue to remove students to a complex system of continuation schools and alternative education facilities. In many instances, these facilities act as warehouses where little instruction takes place.

-

As districts require administrators to reduce suspensions, school administrators turn to in-school suspension and detention rooms. While many administrators voice their intent to use in-school suspension and detention rooms as restorative spaces — and in a few schools, this was true — nothing educative or restorative occurs in a majority of these rooms.

-

While Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) is the most widely adopted alternative discipline intervention and encourages more educative approaches to school discipline, PBIS aligns well with more social control tendencies in schools and co-exists seamlessly with punitive and exclusionary practices. We find that in the schools with the fullest implementation of PBIS, PBIS is the proverbial “carrot” that justifies the continued use of the “stick”.

- Mechanisms and justifications for racially disproportionate punishment vary by school context, but always results in the exclusion and punishment of those students already at the margins of society. In schools serving smaller Black populations, we observe fairly positive school climates for a majority of students but disproportionate punishment and exclusion of Black students. Educators in schools that serve large numbers of Indigenous students, under-resourced and unable to address years of dispossession and disinvestment, often exhibit a deficit-oriented characterization of Indigenous students that justifies disproportionate punishment. For the many schools that serve predominantly Latinx students, educators justify punitive policies by invoking the idea that many Latinx students belong to gangs despite evidence to the contrary.

-

State funding policies and district enrollment and personnel practices exacerbate pre-existing inequities that negatively impact schools in historically disinvested Black and Indigenous communities. Without a significant redistribution of financial and human resources to historically Black or Native schools, mandates not to suspend students translate to permissive and apathetic adult cultures, as many adults forego the intellectual purpose of schooling to get through the day.

-

Organizations committed to multigenerational, insider-outsider organizing that bring together activists, educators, youth and parents in campaigns for racial and economic justice create pockets of hope. In school communities where community advocacy organizations led campaigns with educators to challenge criminalization, militarization, and unequal funding in schools, school discipline reforms extended to restorative teacher-student relationships, relevant and engaging curriculum, and inclusive and safe campuses.

- Finally, we found that a core funder, The California Endowment (TCE), facilitated a convergence of interests, shaped a dominant narrative, and supported the expansion of restorative justice in the state. The Endowment funded a communications effort that contributed to a dominant narrative among education leaders in California that suspensions are not working to change student misbehavior and alternatives are necessary. Unfortunately, the dominant narrative lacked an explicit and overarching structural racial analysis in relation to the framing of the school discipline problem and the kinds of solutions necessary. The Endowment also spotlighted restorative justice as an alternative to punishment and exclusion in the state, and contributed to the expansion of the restorative justice field in California.

While arguably a product of pragmatic policymaking, five years of case study data across the 34 participating schools suggest that recent school discipline reforms in the state shifted the responsibility of supervising youth from law enforcement and criminal justice to schools. However, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx youth remain actively subject to the carceral logics of our imagined change. Yet, our data reveal bright spots, moments of hope, and promising practices that lay the foundation for future education policy, advocacy, and organizing strategies. What is necessary now?

Recommendations

- A coordinated strategy that champions a more explicit structural racial justice analysis in relation to school climate and discipline reform. This strategy must explicitly counter the legacy of racial segregation and disinvestment in Black, Indigenous, and Newcomer communities by investing in schools and community-based organizations in these communities. The strategy must also challenge current school district policies and practices related to funding, attendance, and personnel, that exacerbate existing income and racial inequalities within school districts. Finally, the strategy must support efforts to target and provide alternatives to racist notions perpetuated in schools including deficit-narratives of students and families and racialized notions of safety.

-

A coordinated strategy that begins with an unflinching analysis of how schools, police, the criminal justice system, and other social service agencies form a continuous and interdependent youth control complex or school-prison nexus that encloses youth of color, particularly Black, Indigenous, and Latinx “gang-affiliated” youth in California. While these systems may act or appear to act to support and protect youth, they do so by identifying, surveilling, harassing, and criminalizing a subsection of the population in any community, often creating both the process and justification for the eventual exclusion of these young people from society.

-

A coordinated strategy that treats educators as movement actors, not just movement targets. Teacher and administrators were essential to the success of each of the institutionalization efforts. Where they were strongest, they were well prepared in more restorative approaches through their educator preparation program, aligned discipline to critical pedagogies or leadership philosophies, belonged to wider networks of educators, and were funded to experiment with and share their solutions with others. Teachers, repeatedly targeted, are giving up, with detrimental consequences for young people in schools.

-

A coordinated strategy that continues to strengthen the capacity of multi-generational community-organizing to analyze the social and economic conditions impacting youth and work collectively with parents, youth, and educators to improve them. Locally grounded community organizations are critical to identifying and challenging political, economic, and social injustice. Strong regional and statewide networks of these organizations can support skill-building, analysis, power-building, and coordination.

-

A coordinated strategy that takes advantage of the existing institutional supports within schools for moving school climate, culture, and discipline away from punishment and social control. For example, assistant principals, who have traditionally acted as the dean of students or disciplinarian, have become much more prominent as potential movers and shakers. These positions would be ideal for individuals with deep youth development, youth empowerment, and restorative justice expertise. Coordinated strategies to create new training opportunities, career pathways, and evolving professional expectations targeted at reframing the traditional role of assistant principals are necessary.

-

A coordinated strategy that demands the redistribution of financial and human resources to the schools pushed to the margins of society by antiquated, racist funding and attendance policies. These schools, within historically Black and Indigenous communities, serve the families of our lowest income students. There are a finite number of these schools in the state and our collective responsibility must be to provide the necessary resources to the students and adults in these schools.

Back to top ↑

2. INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, as in many areas of education, school climate, culture, and safety have become a focus of policymaking at the federal and state levels.

Framed in considerably different ways, some federal administrations construe school climate, culture, and safety to mean zero-tolerance discipline policies, greater partnerships between police and schools, an expansion of school resource officers, security cameras, and metal detectors, and increased use of psychotropic drugs to address student misbehaviors.8 Under these administrations, educational programs that pride themselves in teaching a diversifying student body the necessary character or behaviors for work and life are supported by large federal grant programs and flourish nationwide.

Under the Obama Administration, two sets of interests converged9 to take school climate, culture, and safety on a slightly new path. Concerns raised by community activists and civil rights advocates about the growing and racially disproportionate school-to-prison pipeline converged with more pragmatic concerns of state governments over declines in criminal justice budgets caused by the Great Recession (2007 - 2009).10 Nationally, the declining state budgets created an interest convergence to decriminalize youth offenders and demand that schools take on more of the burden of supervising young people. This interest convergence resulted in the creation of what appeared to be a broad national coalition of law enforcement organizations, youth court judges, civil rights organizations, youth and parent organizing groups, foundations, and organizations conducting research and development on alternative approaches. Federal education policy attention to school climate, culture, and safety turned to the reduction of out-of-school suspensions, the adoption of alternative behavioral interventions to redirect misbehaving students, and the hiring of more school psychologists to strengthen mental health supports. Funding for school police through federal Community Oriented Policing (COPS) grants continued.11

Led by parent and youth organizing groups, California has been the incubator for these reform efforts and at the cutting edge of local efforts to challenge punitive and exclusionary school discipline.12 These resulted in significant local wins for decriminalization and new approaches to discipline in some school districts such as Los Angeles and Oakland. Mirroring some of the national trends, a convergence of interests spurred by the Great Recession (2007 - 2009) created a policy window for criminal justice and school discipline reform. While not always on equal footing, this interest convergence in California brought together Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, a law enforcement policy and lobbying organization, with coalitions of community-based organizations, parent and youth organizing groups, and civil rights legal advocates. As a result, among many bills that failed, the California Legislature passed AB 420 in 2013, prohibiting suspensions for willful defiance for students in kindergarten through third grade.

The following year, the California State Legislature required school districts to include plans (i.e., goals, actions, and expenditure allocations) for reducing suspensions and improving school climate and culture within their Local Control and Accountability Plans.12 AB 420 became permanent in 2018 and expanded in 2019 with SB 419, which included prohibiting willful defiance suspensions for fourth and fifth grade permanently and banning them for sixth through eighth graders for five years.

Policies for teacher and administrator professionalization have shifted to support a more holistic vision of student health. The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing revised professional standards to include creating classroom and school environments that promote students’ academic and social well-being in 2009 for teachers and in 2014 for school leadership.13 The California Professional Standards for Educational Leadership (CPSEL) specifically attends to school leaders’ ongoing engagement with discipline systems and data to ensure equity.

In California, The California Endowment (TCE) has been a core funder and one of the key conveners and facilitators of many of these efforts.14 With the help of community partners, the Endowment successfully connected the issue of racially disproportionate use of suspensions to student health and well-being in schools, striving to create more positive and supportive learning environments that promote life-long health and wellness in all students. Since 2010, the Endowment provided $1.75 billion in funding and initiated a diverse set of strategies, including organizing, youth development, communications, coalition-building, capacity-building, and research.15 Other reports describe these efforts in more detail.16

Committed both to funding entities involved in policy change, as well as the translation of these policies into sustained institutional change within schools, the Endowment’s statewide School’s Team and their place-based Building Healthy Communities (BHC) Team have experimented with a variety of funding and support strategies aimed at institutionalizing non-punitive and non-exclusionary school discipline practices in schools.17

Among other statewide strategies, the Endowment provided a total of $1 million in competitive grants to school districts in the Central Valley of California to adopt more positive or restorative school disciplinary systems.18 Grants ranged from $60,000 to $200,000 per district and funded activities such as teacher and parent training in restorative justice (RJ) and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), teacher release time, PBIS materials, and coordinators. Along with funding, school districts were invited to participate in a regional Leadership and Learning Network. Beginning in 2018, TCE has also funded Restorative Justice for Oakland Youth (RJOY) to regularly convene a virtual statewide learning community on restorative justice, providing a space for educators, restorative justice practitioners, and researchers to build and share expertise.

Within the Building Healthy Communities place-based initiatives, program officers in 14 geographic regions in California continued to fund and support local education justice hubs, coalitions, and particular school initiatives.

These activities fell into four primary funding strategies:

- Community organizing efforts, which resulted in the adoption of positive school discipline policies in six school districts, serving a total of more than 331,40319 students.

- Legal advocacy, which resulted in at least one case brought against a school district in the state for discriminatory school discipline.

- Districtwide school discipline initiatives, which funded individual school district central offices to lead, organize, and coordinate school discipline reform efforts.

- School-level experimentation, which funded school leaders and teams to study, select, train, and experiment with alternative approaches to school discipline.

What has been the impact of these efforts?

Relevant quantitative data show mixed and sometimes confusing results. As a whole, statewide school discipline data show an overall decline in suspensions, particularly between the 2011-12 and 2014-15 academic school years.20 During the first few years of collecting and reporting statewide suspension data, suspension rates fell from an average of 5.8% to 3.8% in the state. However, statewide suspension data show that suspension rates have remained relatively stable, ranging between 3.5% and 3.7% every academic year since.

Perhaps more puzzling, however, is that more nuanced school climate indicators such as those collected by the California Healthy Kids Survey show that in middle schools, violence, victimization, bullying, and harassment have improved; yet, school connectedness remains stable at roughly 60% of students responding favorably, and 40% responding neutrally or negatively.21 Four other key school climate indicators — Caring Adult Relationships, High Expectations, Opportunities for Meaningful Participation, and Perceptions of School Safety — declined between 2011 and 2019. It is important to note that only 40% of middle school students in 2011 - 2013 reported having opportunities for meaningful participation in school, and this number fell to just 35% in 2017 - 2019. Middle school students reporting favorable feelings of school connectedness and the presence of caring relationships hovered around 63% during the same period. Perceptions of school safety increased between 2013 and 2017 and declined between 2017 and 2019.

These data suggest that even as schools reduce suspensions, student perception of school climate, culture, and learning are not great. These quantitative data raise additional questions — questions that qualitative data and methods are particularly adept at answering.

Research Questions:

| 1.

How have school disciplinary cultures (i.e., narratives, norms, and practices) changed in the subset of California schools in this study? |

2.

What strategies and conditions have supported efforts to move away from punitive or exclusionary school discipline practices? What obstacles remain? |

3.

What role has an ecosystem of community-based and advocacy organizations in California, and a core funder, The California Endowment, played in these efforts? |

The qualitative data in this study allow us to examine the depth of actual changes; what these changes in school discipline mean or do not mean for students, families, and teachers’ experience of school climate, culture, and safety; and what strategies have led to particular outcomes.

These lessons intend to inform those at different levels and places within the system, and recognize that systemic change is difficult, necessary, and a perpetual place of struggle — and joy. This study builds upon the Central Valley School Discipline Learning Project, a developmental evaluation undertaken as a partnership between TCE program managers, learning & evaluation managers, and an interdisciplinary team of researchers. The research design was expanded to include Northern and Southern California, and schools not directly funded by the Endowment. The resulting study is likely the largest qualitative comparative study of school climate, culture, and discipline in the state.

This team of researchers and grantmakers co-created the research design, deciding upon research questions, sampling methods, and data sources. The strength of developmental evaluations over traditional evaluations is that the process embeds researchers within a work team to produce context-specific research that can be utilized immediately to inform grantmaking strategies and educational efforts.22 Developmental evaluation processes encourage curiosity, honesty, and a culture of learning within work teams.

Back to top ↑

3. RESEARCH DESIGN

To examine the impact of the diverse grantmaking strategies utilized by The California Endowment’s (TCE) Building Healthy Communities (BHC) place-based strategy and the impact of statewide strategies, researchers used a qualitative comparative case study method. Researchers identified case study districts within the BHC program and chose five additional case study districts outside of BHC as matched comparisons.

Researchers solicited participation from school districts that shared size, demographic, and geographic similarities with the school districts in BHC. Not all school districts solicited participated in the study. The resulting districts vary in geographic region, size, and demographics of students served.

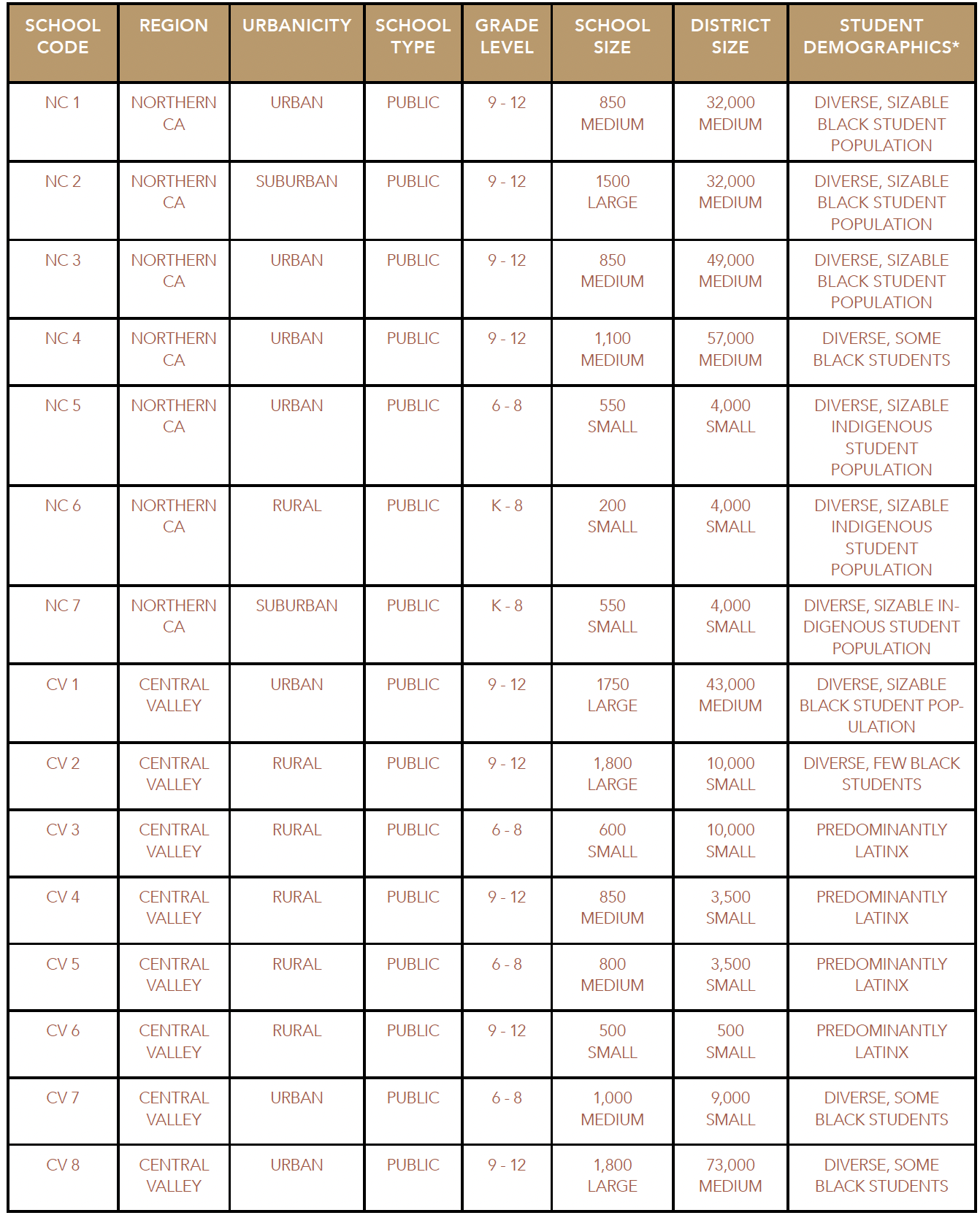

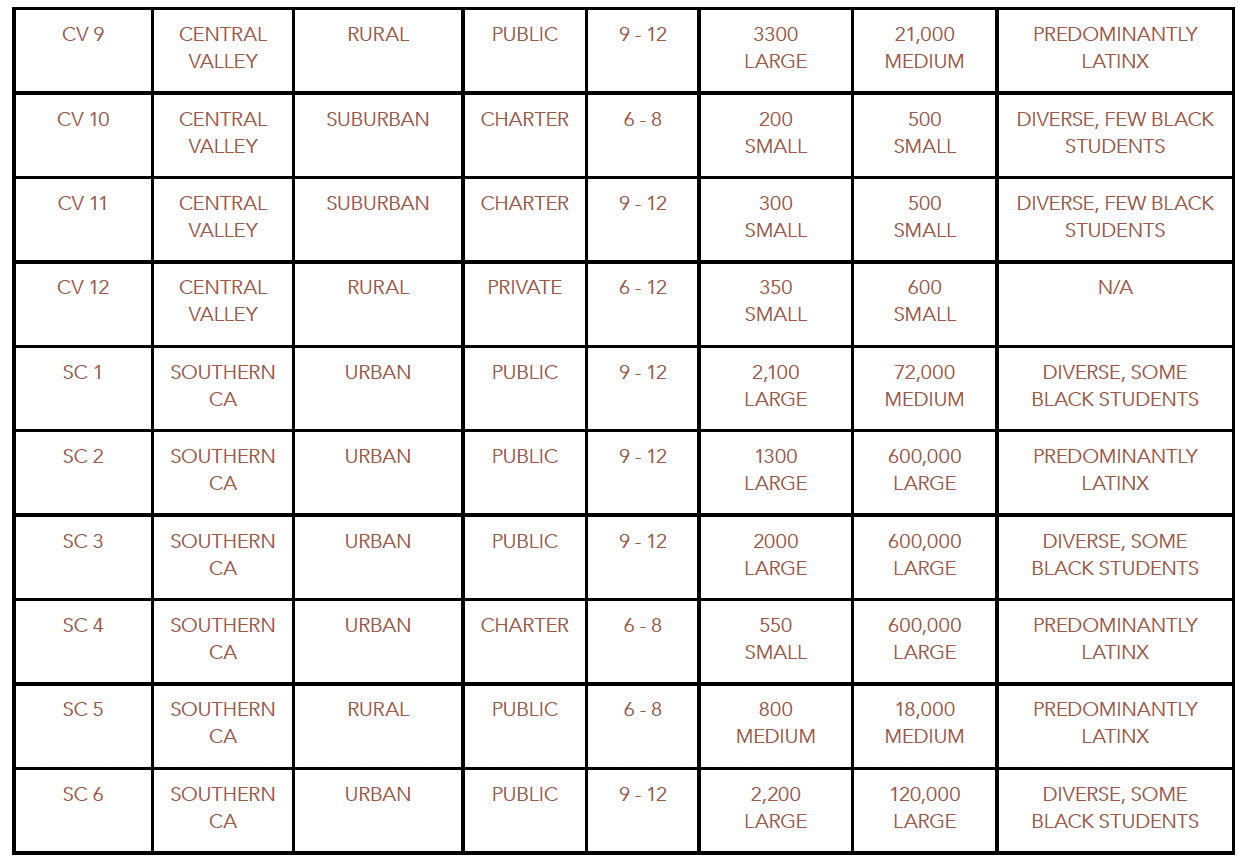

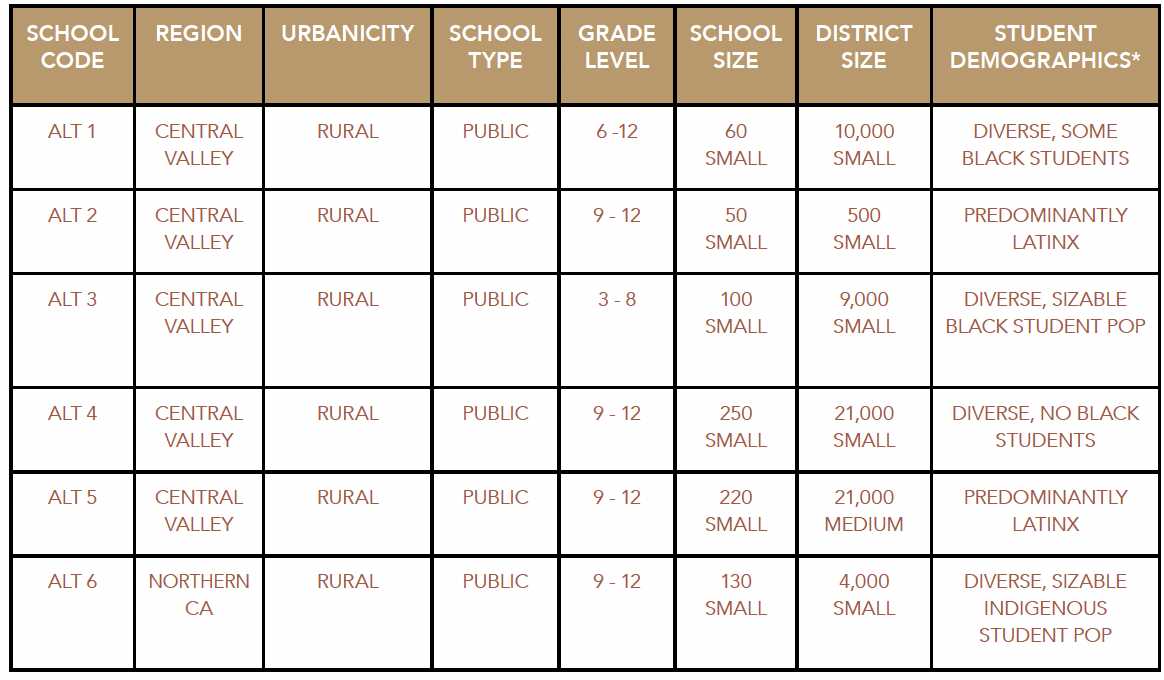

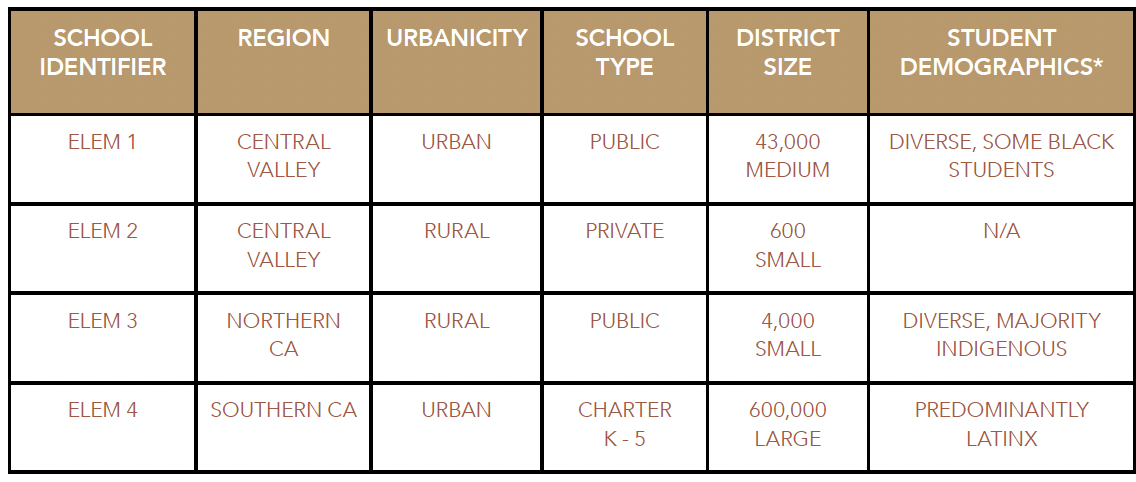

Focal secondary schools within the case study districts were selected in conversation with district or community leaders. These schools often represented what district and community leaders believed to be “furthest along” in their efforts to move away from punitive and exclusionary discipline and/or in implementing alternative approaches such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) or restorative justice (RJ). Focal schools were middle and high schools, since they are shown in research and in the quantitative school climate data to be the schools with the greatest level of punitive and exclusionary discipline. Of the 31 focal schools in our sample, 16 were comprehensive high schools, nine were comprehensive middle schools, and six were alternative education facilities (i.e., continuation schools, community schools, and independent studies facilities). We visited four additional elementary schools that we did not formally include in the analysis of this report.

Researchers terminated data collection earlier than intended due to the worldwide coronavirus pandemic, which abruptly closed schools in March 2020. The resulting 31 focal schools differ along important conceptual dimensions that reflect the diversity of a large state like California. The focal schools vary in urbanicity, size, district size, demography, geography, and political-economic context. As a whole, 15 focal schools were rural, four suburban, and 12 urban. Fifteen schools were small (less than 600 students), seven medium-sized (600 – 1,100 students), and nine large (1,300 – 3,300 students).23 District size also varied, with 17 focal schools in small districts (500 – 10,000 students), 10 in medium districts (21,000 – 72,000 students), and four in large districts (120,000 – 600,000 students).

We found that the student demographics for our focal schools fell into two broad categories: either predominantly Latinx, which we defined as having student bodies of over 90% Latinx students, or diverse.24 We also found it useful to differentiate the “diverse” schools further to describe the presence or absence of Black and Indigenous students given the ways in which policing and suspensions disproportionately impact Black and Indigenous communities. We considered 10 focal schools predominantly Latinx, nine focal schools as diverse and enrolling a sizable number of Black (~20%) or Indigenous students (~15%), seven focal schools as diverse and enrolling some Black or Indigenous students (~ 5–10%), and five diverse schools enrolling few, if any, Black students. Researchers located 17 focal schools in the Central Valley region of California, eight focal schools in Northern California, and six focal schools in Southern California. See Appendix A for a summary table describing focal schools.

Case study data consisted of interviews with district central office administrators, school site leaders, school site staff, teachers, and community-based organization leaders associated with school discipline efforts when available. Researchers also held focus groups with students. Where possible, we requested to hold separate focus groups with student leaders and students who had a great deal of contact with the disciplinary system of their school.

In all comprehensive schools, researchers shadowed eighth or ninth graders through their school day, observing class periods, passing periods, lunch, before and after school, and assemblies. Researchers generally shadowed students on different academic tracks. In total, researchers spent a total of approximately 191 researcher-days collecting data and observed approximately 291 class periods. See Figure 1 below for a chart summarizing data sources.

The research team coded interview transcripts, focus group transcripts, and observation notes using Dedoose, a qualitative data analysis software. Researchers wrote within-case reports for each school and met across teams to locate each school on the School Climate and Culture Quadrants and discuss themes and comparisons across cases.25

We also collected demographic data such as race, gender, years in education, hometown, and role for each individual. For each focal school, researchers reviewed school websites, School Accountability Report Cards, and pamphlets to capture the school’s mission, principles, and goals; and gathered publicly accessible school discipline data from the California Department of Education.

Researchers wrote within-case reports for each school and met across teams to discuss themes and comparisons across cases. The cross-case analysis was organized in two ways: 1) visualizing the location of each focal school on a School Discipline Purpose & Approach Quadrant and 2) summarizing patterns of interest using cross-case matrices.

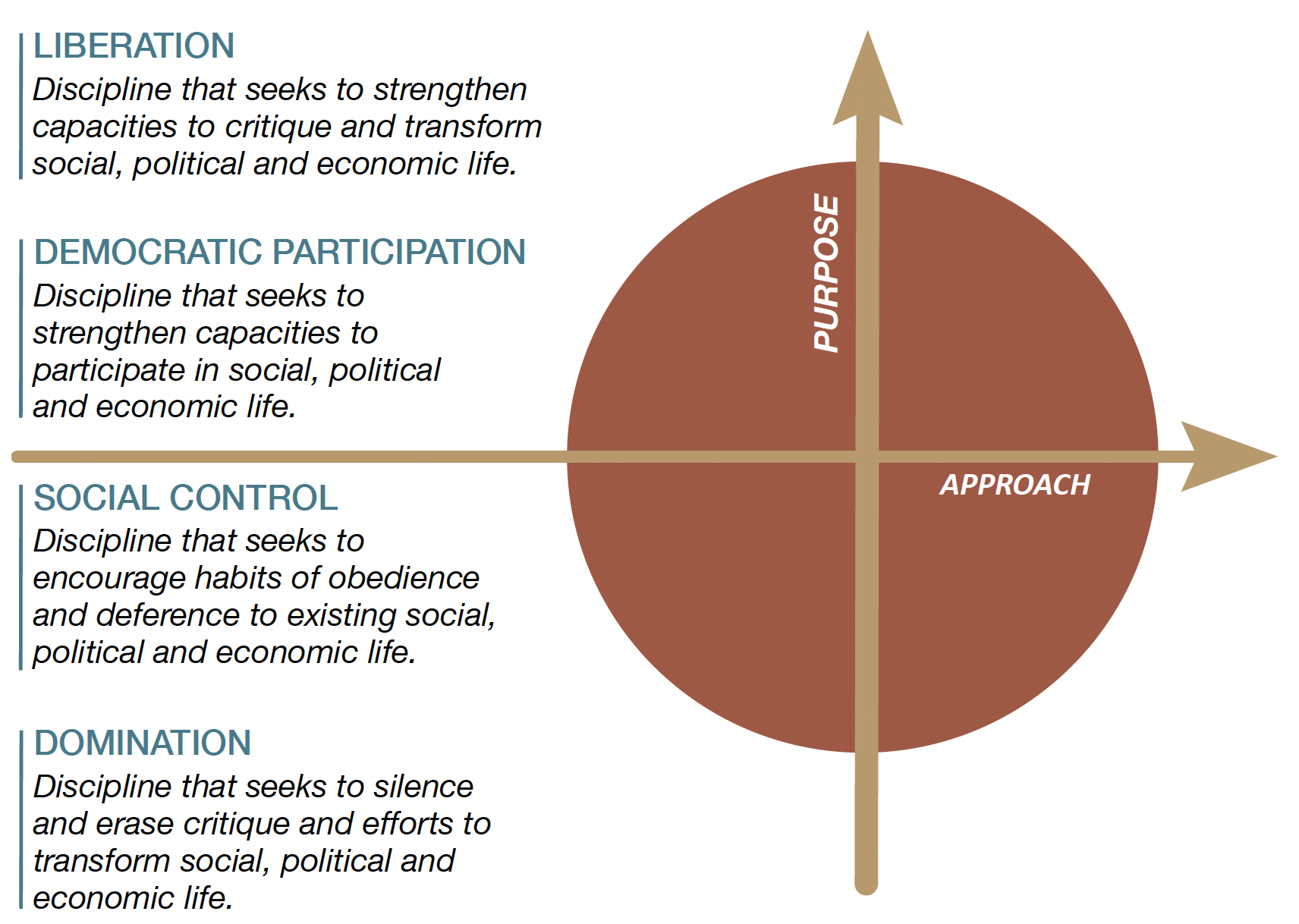

First, to visualize and compare case studies, researchers used case study data to chart the location of each comprehensive school on the School Climate and Culture Quadrants. The School Climate and Culture Quadrants emerged from early observations of school discipline practices as a useful visualization of the conflicting purposes of school discipline and manners of achieving school discipline that often co-existed in the same school.26 We found that the quadrants also allowed us to better visualize the connection between how the school was maintaining discipline and for what purpose, which was inextricably linked to teaching and curriculum.

PURPOSE FOR ACHIEVING SCHOOL DISCIPLINE AXIS

Along the vertical axis, we plotted the primary purpose of school discipline evidenced by our data. Toward the bottom, we charted the schools where the primary purpose of school discipline was domination or a discipline that sought to silence critique and efforts to transform social, political, or economic life. Imagine schools that expect students to behave, even when conditions are unfair, punish students for asking questions, and expect students to perform task-oriented work silently and without complaint. Students’ identities and autonomy were treated as inappropriate or unacceptable in these schools, and school disciplinary systems were designed to stamp them out. For example, American Indian boarding schools27 exemplify this educational philosophy, historically, in American schooling.

Moving up on the vertical axis, the primary purpose of school discipline became about social control, which was less about stamping out student identity and autonomy, but more about inculcating obedience for maintaining the existing social, political, and economic order. Cultural difference was tolerated at the margins so long as students were quiet, produced, behaved, and did as they were told.

Moving further up the vertical axis, the primary purpose of school discipline became about democratic participation, or the teaching of young people to successfully participate in our current social, political, and economic systems. Developing skills and respect for voting, representative government, and the legal system were translated into student government, conflict mediation, and youth court. School discipline in these schools provided opportunities for youth participation in the process, however, the inherent power imbalances and injustices within these systems remained unquestioned.

Finally, at the very top of the vertical axis, the primary purpose for school discipline was to support education for liberation, or discipline that seeks to strengthen capacities to critique and transform social, political, and economic life. This concept was articulated by popular educator, Paulo Freire, and taken up by critical educators around the world.28 Imagine a school where students are supported to understand their circumstances, analyze the push and pull of systemic and institutional factors that created those circumstances, and identify short- and long-term goals to change the systems that disrupt their daily lives. A school that prioritizes this purpose would be designed to support youth to “be the change” in the world through its curriculum, teaching methods, organization of the school year and school day, and yes, its discipline systems.

Along the horizontal axis, we charted the approach for achieving school discipline, which has evolved some in recent years, though it co-exists in many of the schools in this study. We plotted exclusion on the far left of the horizontal axis to describe discipline approaches that remove students from academic activity when they are deemed disposable or ineducable. Removal to continuation schools and locked-down educational facilities exemplified this approach. Toward the right, punishment, or discipline that attempts to reform students through fear, shame, or deprivation, does not dispose of students but punishes students into conforming. Punishment spanned various practices ranging from sending students out of class — which is both a form of exclusion and a form of deprivation and punishment — to verbal reprimands meant to correct behavior.

Moving further right, educative through extrinsic approaches to school discipline attempts to teach students appropriate behaviors and encourages these behaviors by using extrinsic motivations such as rewards, recognition, and material benefits.

At the furthest right, educative through intrinsic approaches to school discipline embeds discipline in academic activity and is rooted in building intrinsic motivations for self-discipline. This looked like a student meticulously detailing an art piece, a class getting lost in a project, or high school students creating an experiential learning curriculum for their younger peers.

Through the School Climate and Culture Quadrants, which we derived from educational theory, the history of school discipline, and observations of contemporary practice, the research team visualized where schools were in comparison to one another (i.e., the location on the Quadrants). We also plotted the range of disciplinary practices observed or disciplinary purposes expressed through the shape of the plot. Finally, we used arrows to describe the direction that a particular school appeared to be moving on the quadrants. Since the case studies were not longitudinal, the arrow is only used to indicate clear evidence of changes to come (e.g., termination or creation of positions, changes in funding, changes in policy or introduction of new procedures).

In addition, the research team analyzed patterns and themes across cases to create matrices which included summaries of qualitative data by codes and subcodes (e.g., leadership characteristics, implementation strategy, alternative approach adopted, presence or absence of police, institutional supports, institutional obstacles); TCE dimensions of interest (e.g., within or outside BHC, TCE funding strategy, etc.); and existing quantitative data, like school size, school demographics, suspension, and expulsion rates. The matrices identified and confirmed patterns and themes.

Back to top ↑

4. THE STATE OF NON-PUNITIVE SCHOOL DISCIPLINE EFFORTS IN CALIFORNIA

How have school disciplinary cultures changed in this subset of California schools?

This is not to say that recent efforts to minimize the use of suspensions, implement alternatives to punishment, and invest in student supports are not working. It is to say that in many places where there was evidence of important shifts away from punishment and exclusion, old systems of punishment and exclusion existed, and even where there had been significant gains, we found these gains could be quickly eroded. In the process, there are important lessons that we heard and observed that can inform the continued work in this arena.

As detailed in the introduction, numerous federal and state policies have shifted away from zero-tolerance school discipline as a result of decades of community and youth organizing. These policies began as grassroots efforts in the early 2000s and impacted federal and state policy during the Great Recession. Described more fully in other reports, the Endowment has played a significant role in conceptualizing the Building Healthy Communities approach to place-based advocacy, and has been a key funder and convener of community-based and advocacy organizations who advance health-promoting policies at the local and state levels.29

From our sample, coalitions of community-based organizations and advocacy groups successfully passed districtwide policies that promoted alternatives to suspension in seven of the 17 school districts in our study. One local policy prohibited suspensions under the state category of willful defiance, codified student, parent, and guardian rights to discipline data, established a district team and accountability process to ensure implementation of Schoolwide Positive Behavior Interventions and

Supports (SWPBIS), and identified restorative justice (RJ) practices as alternatives to conflict.30 Another district policy laid out a Response to Intervention framework that included PBIS and RJ as strategies to reduce punitive discipline.31 It also included a Wellness Policy committed to social-emotional learning. Yet another school district adopted a School Climate Bill of Rights that affirmed stakeholder rights to train, implement, and evaluate restorative practices. Some policies also created advisory committees and a central office department dedicated to supporting schools implementing restorative practices.32 In numerous Local Control Accountability Plans (LCAP), school districts have committed to building positive school climates with an array of strategies, including PBIS and RJ.33 These policies are characterized by explicit commitments to a districtwide move away from punitive approaches and support of PBIS and RJ as interventions and strategies that promote a positive school climate.

Influenced by TCE Strategies

LEADERSHIP NARRATIVES ECHO POLICY NARRATIVES

We found that changes in federal and state policies, particularly those that required the collection and reporting of suspension and expulsion data, influenced a change in the narratives of school and district leaders. Among district and school leaders (i.e., superintendents, district office administrators, principals, and assistant principals), we found a pervasive narrative that zero-tolerance state policies regarding suspensions were not working and that suspensions are not a useful tool to foster student success. Superintendents and principals in all regions of California echoed this. Below, we provide some illustrative examples.

| Northern California Administrator: “I think the good is that we’re not suspending folks as much for things that really can be mediated here on campus — defiance, disrespect, disruption…. Especially at our school, we can’t continue to exclude folks, because we already have a struggle with students being under-credited. If they’re home they’re not going to have access to the learning. I feel like in a school like ours, that resolution is very positive.” |

Central Valley, California Administrator: “I’ve seen the whole swing from zero-tolerance to now. The last five or six years, the message is to do something besides suspending and expelling kids, to cut down on it. I think it’s been a good move. So that’s been the big change. And some of it was state, and then at our district level we have a new superintendent, associate superintendent, and they really believe in it. They’ve pushed it on to the principals. From my office, I support it. I’m kind of like a gatekeeper in a way. The whole philosophy is to reduce suspensions.” |

Southern California Administrator: “I’ve suspended my share of kids and suspension doesn’t always work. If they’re chronic suspensions of the same kids, it doesn’t help by just kicking them out of school for a few days and they come back and they don’t have any supports or structures for them to cope, to avoid making some of the mistakes in the future.” |

These narratives about school discipline align with those put forth by TCE-funded advocacy efforts. What’s important to note is that most school administrators described these changes as unshackling educators from earlier state policies that required the suspension and expulsion of students.

We found that district and school leaders’ critiques of suspensions primarily revolved around the ineffectiveness of suspensions to change student behavior and the importance of maximizing instructional time. We heard little mention of the other concerns that first animated community activists, scholars, and advocates to demand change. We did not hear school administrators, teachers, or other school staff talk about the ways that suspensions and expulsions are often racially disproportionate.

Absent too were any concerns about the expansion of school police and other technologies, like surveillance cameras, that made schools more like prisons.34

These findings suggest that currently, district and school leaders widely share the narrative that emerged from TCE’s communication efforts. Those efforts polled likely voters to craft a ‘winnable’ message for state policy change. The policy narrative that suspensions are not working and that suspended students lose instructional time and are not being properly supervised, has taken hold among administrators. Yet, what are the implications for this framing of the problem, and the loss of the broader community concerns about the school-to-prison pipeline or school-prison nexus?

We explore this more in subsequent sections.

SUSPENSION RATES HAVE DECLINED, AND MORE DRAMATICALLY FOR SCHOOLS SERVING THE MOST MARGINALIZED STUDENTS IN THE STATE

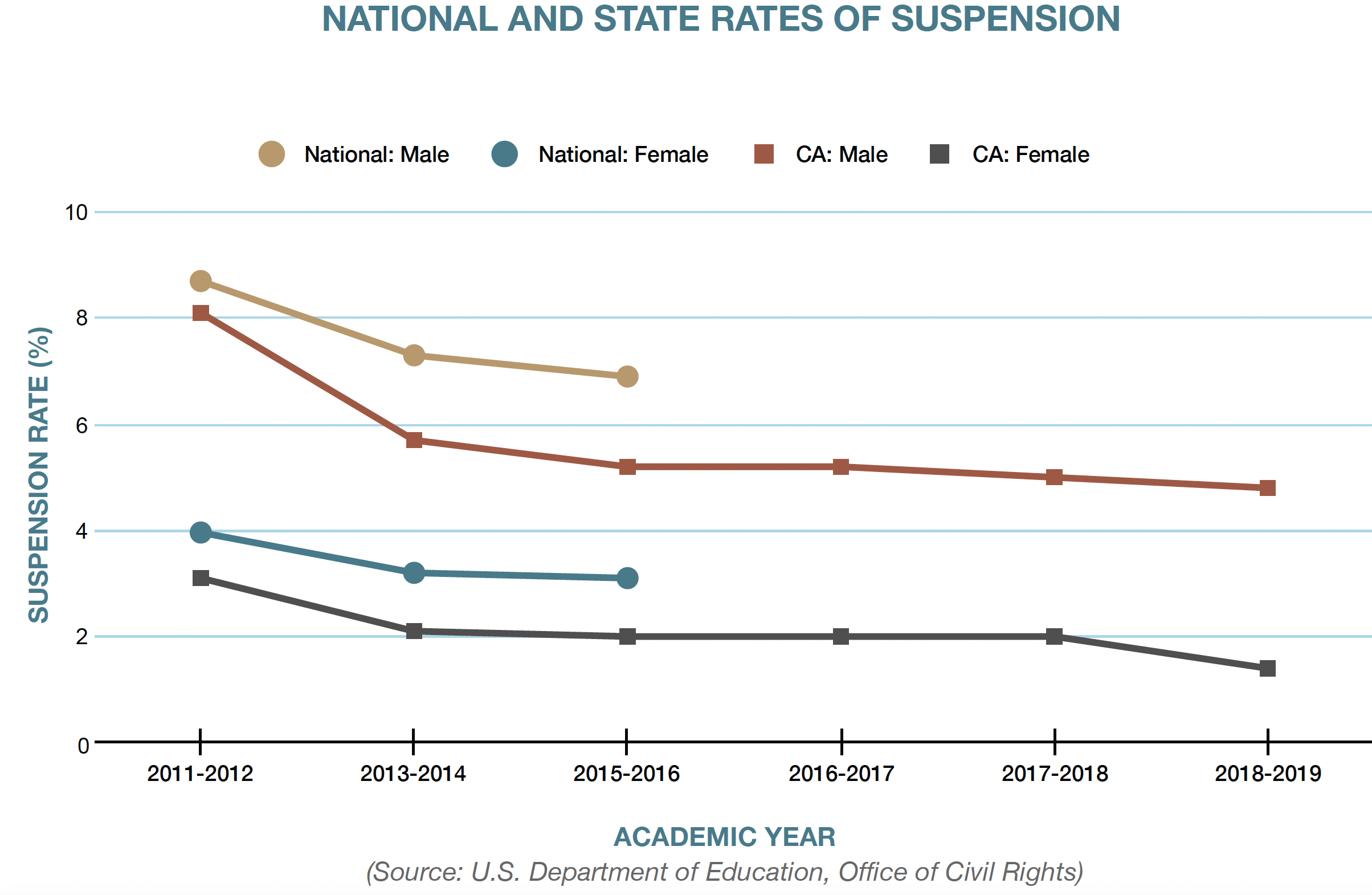

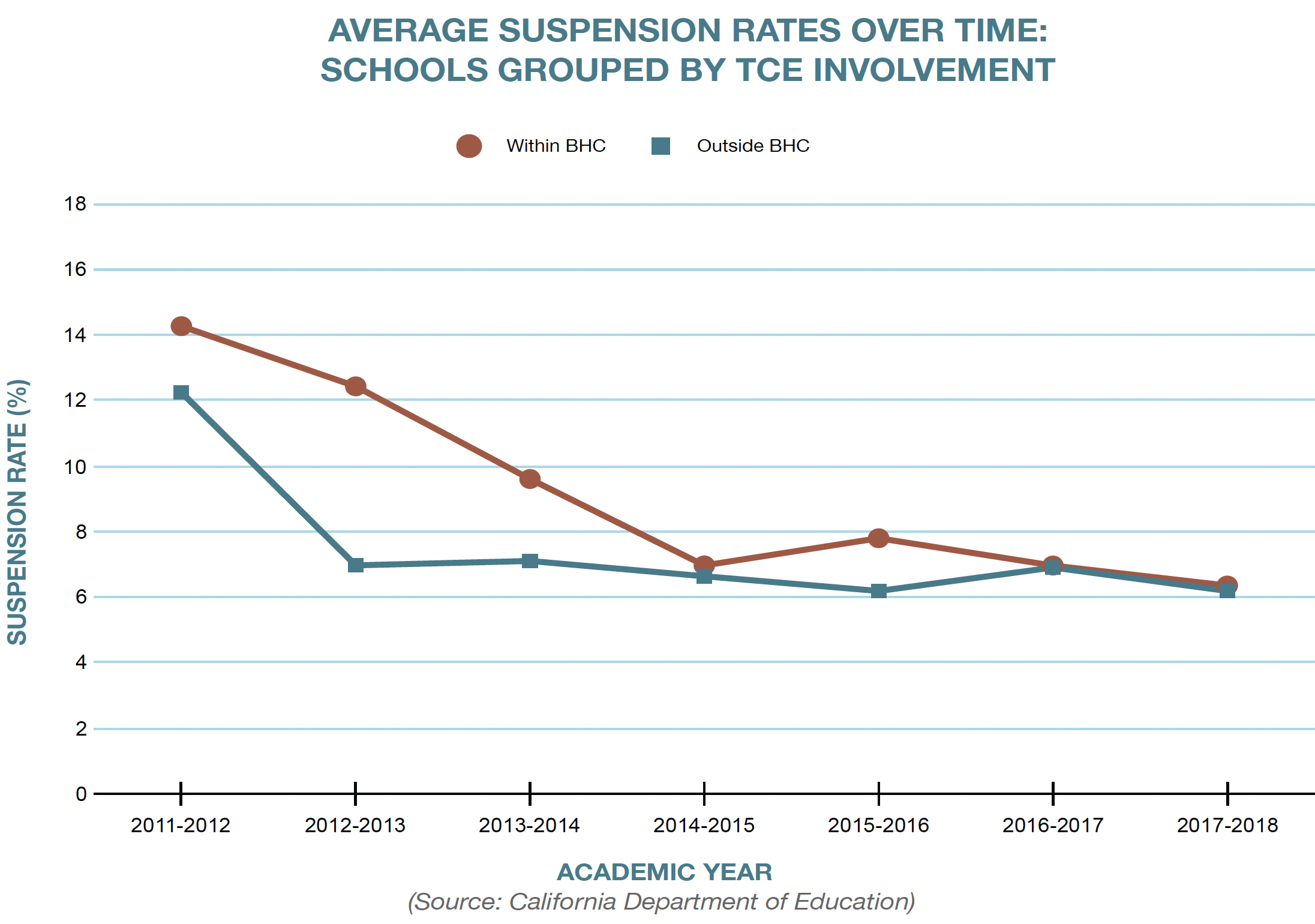

Suspension rates in California have declined and leveled off, matching a similar pattern nationally (see Figure 5). Average suspension rates in California remain lower and have declined further than national rates of suspension.

Unfortunately, the termination or temporary halting of the Civil Rights Data Collection under the Trump Administration prevents a complete analysis of how California compares to the nation since 2016. The Biden Administration’s commitment to reinstating Obama-era school discipline guidance may lead to the resumption of federal school discipline data collection.

Among the focal schools in our study, we found dramatic declines in suspension rates. Twenty-six out of 30 schools (or 86%) within our sample with publicly available suspension data experienced a decrease in suspension rates between the 2011-12 and 2018-19 academic school years (AY). The four schools that experienced an increase during this time were small schools, two of which were small comprehensive schools that regularly had low suspension rates (below 6.2%) and two of which were alternative education sites with suspension rates that fluctuate a great deal from year to year.

This trend of declining suspensions is true regardless of TCE involvement. We examined the change in suspension rates from 2011–2019, comparing schools located within one of the Building Healthy Communities (BHC) sites to schools not located within a BHC site.35

Among the focal schools located within BHC, average suspension rates (calculated as the percentage of enrolled students suspended one or more times in the given school year) dropped from an average of 14.2% to 5.9% between AY 2011–12 and AY 2018–1936. Among schools located outside of BHC sites, average suspension rates declined from 12.3% to 4.9% during the same time.

The dramatic decline in suspension rates was particularly pronounced in the Central Valley schools in our study, where suspension rates fell from more than 25% in several schools to less than 10% between 2011 and 201937. Interview data suggest that many schools simply stopped suspending students for small infractions. For example, in one school, a school leader explained that in previous years students who were tardy would be given Saturday school, and then if they did not attend, they would be suspended. Ending this practice reduced their suspensions from approximately 1,200 students in AY 2009–10 to approximately 200 suspensions two years later.

Consistent with overall state data, schools outside of BHC show a dramatic drop in suspensions in the first year after state data collection, and remain fairly constant thereafter. These dramatic declines in suspension rates precede the implementation of alternative approaches in most schools and precede a majority of the state and local policy reforms. This suggests that in the focal schools outside of BHC, the collection and reporting of suspension numbers alone drove much of the declines in suspensions. Our qualitative data support this. Educators often discussed pressure from district central offices to not suspend students. However, without additional resources, declines in suspensions did not necessarily translate into more supportive or educative alternatives in these schools. We describe this in more detail below.

In contrast, focal schools within BHC sites show a slower but steady decline over four consecutive academic years between AY 2011–2012 and AY 2014–2015, before remaining fairly stable. It is important to note that TCE strategically chose places because they are some of the most economically and politically marginalized communities in the state; thus, the schools also tended to have higher levels of punishment and exclusion. Notably, the gap between the schools within BHC sites and those outside has closed, suggesting a more significant move away from punishment and exclusion for those historically most pushed to the margins of society.

We found a vast majority of schools to be clean, organized, and safe spaces for most students. Yet, in these schools, the primary purpose of discipline remained to ensure that students were in class, seated, and quiet without questioning authority. On the quadrants, this was demonstrated by a majority of schools falling below the X-axis.

We observed security guards hurrying students through hallways and to class. We shadowed students into classrooms where teachers taught lessons towards specific recognizable standards and spoke to students in firm but respectful ways. In a vast majority of classrooms, we found teachers who saw their role as preparing students primarily for jobs where they will have to listen and behave. One teacher provides an illustrative example of the most prevalent perspective held by teachers:

“I don’t send kids out. I try to handle as much as possible unless it’s like the kid walked out or it’s a situation where they directly curse at me. Then that has to be handled. Basically, what I do is just educate. I really let them know, ‘Okay. Respect has to go both ways. It cannot be, just because you’re a child, it’s not going to be okay for you to just curse at me and get away with it.’ There’s situations where kids ... just it didn’t work out. I made arrangements for them to switch classes. Especially ninth and 10th graders, they’re very emotional and it’s all about whether I like you or not. It’s like it’s not necessary. You’re going to have a boss you don’t like. There’s a lot of colleagues I work with I don’t like, but I still have to respect them and work with them, you know?”

Thus, within most classrooms we visited, instructional approaches emphasized rote learning of concepts that were not made relevant to students’ lives or experiences. Student-to-student interactions around academic content were limited; substantive, critical engagement with each other’s ideas and learning were even rarer. Teacher and student interactions were primarily one-way, directed by the teacher and students demonstrating content acquisition. While rote learning was more pronounced in rural schools, this ‘banking method’ of education continued to predominate in the classrooms we visited.

The most frequent misbehaviors occurred when students questioned the purpose of learning a particular standard, refused to do as they were told, socialized with peers instead, or used their phones. We found that the recent school discipline reforms to reduce suspensions and implement alternatives like PBIS or RJ provided educators with more tools for addressing these behaviors with educative and non-punitive means but did not address the underlying tensions in the classroom.

To describe more fully the range of school climate, cultures, and disciplinary systems we observed in our sample of schools and to visualize the direction in which different strategies are shifting these cultures, we utilize the School Climate and Culture Quadrants that we described in more detail in the Research Methods (pp. 16 - 17).

We found that regardless of TCE engagement, whether within BHC or outside, schools were widely distributed across the School Climate and Culture Quadrants. However, we plotted most schools in the bottom half of the Quadrants indicating that the purpose of discipline remains primarily for social control. As a result, in almost all locations, schools added alternative discipline practices onto existing exclusionary or punitive measures. Thus, schools continued to practice both punitive and educative disciplinary approaches. We describe these findings in more detail below.

BRIGHT SPOTS EXIST

Throughout the state and in almost every school, we observed particular bright spots or individual classrooms or interactions where instruction and alternative discipline approaches came together to create intrinsically educative academic experiences for young people for either democratic, participatory, or liberatory purposes. Unfortunately, these bright spots did not equate to whole-school disciplinary systems that supported all students.

For example, in one continuation school in a rural area, inspired by students’ interests, the principal implemented an experiential learning program around a school farm that included livestock and a garden. In his mind, instruction and school culture are inextricably tied together:

“It’s just trying to promote the culture here, being a restorative culture, a positive culture, we’re all in this together, whatever-it-takes-type culture. And, more of a culture of ‘Well, why not?’ Not, ‘No that can’t happen.’ You want to build a farm? Well, why couldn’t we? Alright. We got folks that are Ag folks.”

In this school, students who had been unsuccessful in comprehensive schools in the district built a farm and a ropes course, and created an entire day of experiential learning for elementary school classes in the district.

In another high school, educators created a ninth grade house in which ninth graders experienced a school-within-a-school where cohorts of students moved together. Ninth grade teachers collaborated on academic content and discipline practices, so students experienced coherence across subject matter and consistency in expectations across their classrooms. This school offered an exemplary model of weaving restorative justice practice with academic content. A teacher in the ninth grade house explains:

“We do an activity called Columbus on Trial. And the way that it was designed by Bill Bigelow from Rethinking Schools is the jury decides what to do with Columbus. And in the past, [students were] like kill Columbus, hang his men. But now we changed it to — we integrated RJ practices by asking the kids, ‘Well how do they make things right now? You can’t kill them, and you can’t hang them.’ So, the kids start asking for reparations. You need to make up all the harm that you’ve caused.”

These examples of the creative weaving of intrinsically oriented and educative discipline practices with instruction provide examples of the kinds of education we could be offering in our state. We describe more examples of these bright spots in a separate brief available in the Appendix.

Yet, these bright spots were not the norm.

SCHOOLS WITHOUT AN ARTICULATED ALTERNATIVE DISCIPLINE APPROACH DEFAULTED TO PUNITIVE, EXCLUSIONARY, AND SOCIAL CONTROL ORIENTATIONS

Schools without school-articulated discipline approaches tended to be in the punitive and social control quadrant. In some of these schools, there was no plan because the school was essentially chaotic. Teachers lacked a sense of collective responsibility for the school. For example, one teacher says of their responsibility for monitoring school hallways,

“I think, ‘Okay I need to stay off that floor for a while,’ because I can’t pretend I don’t see behavior, and then it just makes for a horrible day.”

In schools that lacked a common school vision for school climate, culture, and discipline, teachers tended toward permissiveness or avoidance to make it through the day.

In these schools, academic busywork, such as copying notes, characterized most classrooms. In a sense, the teachers had given up on the school and retreated to their classrooms. In other schools, the district officially adopted an alternative discipline approach through top-down implementation mechanisms, so, teachers resisted and little evidence of any systematic alternative discipline practice was observed.

WIDESPREAD ADOPTION OF ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO DISCIPLINE MOVE SOME SCHOOLS TOWARDS MORE EDUCATIVE MEANS OF SCHOOL DISCIPLINE

While the underlying assumptions and values of alternative disciplinary approaches differ, what is common across Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), restorative justice (RJ), and Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) is that they move discipline from a legal rule-following endeavor to a more educative one.38 In schools where implementation strategies and conditions were supportive, we found evidence of more educative approaches to discipline. However, we also found that in many schools where implementation strategies and conditions were not supportive, the adoption of PBIS and RJ was only in name.

In the PBIS model, acceptable behaviors are described and taught in lessons at the start of school and reiterated throughout the year. Successful enactment of those good behaviors is rewarded, and unacceptable behaviors are corrected. While schools in our sample demonstrated different levels of success and institutionalization of these practices, most schools, at minimum, clearly articulated common school rules and expectations to students.

The RJ model uses conflict, misbehavior, and transgressions as moments for building empathy and understanding, and teaches individuals to recognize and repair the harms they have caused. These lessons occur through the facilitation of restorative justice circles in which participants take turns sharing their stories, experiences, and thoughts in response to prepared prompts, such as, “Who has helped you become who you are?”, “How were you impacted by what happened?”, “How did it make you feel?”, “What could you do to make it better?” Social and Emotional Learning teaches desirable traits and skills in curricular units, such as honesty, integrity, growth mindset, self-discipline, and empathy. Students are taught and then expected to practice these traits and skills. In each of these models, school discipline is treated as one element of student learning and development into adulthood. This common element provides new tools so that educators, given the motivation, skills, and time can replace punitive or exclusionary practices.

We found that when schools more fully practiced PBIS and RJ, their disciplinary practices were more educative. In one school practicing PBIS schoolwide, a teacher explains how expectations are taught explicitly during orientation and how teachers reiterate them in class.

“They’ll have orientations and they’ll have presentations ready and they’ll talk about uniforms, expectations, requirements, policies and sports. And just talk about the four major, we call them schoolwide rules, be safe, be respectful, be responsible, appreciate differences. And then I try to enforce that in the beginning of class, just to share examples and then that’s the major theme as a school. And then they do address it in staff meetings.”

In these schools, students are taught what it means to be safe and respectful in classrooms, hallways, and the library. In this way, school discipline is educative in nature.

Through interviews with administrators, teachers, and students, we found evidence that they ascribed positive changes to school climate and culture to the adoption of PBIS and RJ, usually with the biggest changes in school climate and culture occurring when in conjunction with smaller enrollments, small learning communities, and other structural changes. We discuss these findings more in the next section when we discuss the impact of adopting particular alternative approaches.

In many schools that officially adopted PBIS and/or RJ, lack of resources, organizational infrastructure, or underlying relational conflicts created obstacles for implementation and institutionalization (see section on Supportive Strategies & Remaining Obstacles). In these schools, the adoption of these alternative programs was often in name only, and we observed little evidence of these practices in classrooms. One exchange with a teacher in one of these schools illustrates this:

“[INTERVIEWER]: What’s your experience with restorative justice at this school?

[TEACHER]: I know that we had a person doing restorative justice in the past, he was the person, the lead. I know that the Dean now uses it. I’ve never done it in my classroom. I’ve sent students out to a restorative justice circle. But I’ve never really, I’ve never done it.

[INTERVIEWER]: So, you weren’t trained in it or anything like that?

[TEACHER]: Were we trained? If we were, it was like a one-day thing. I don’t really remember it.

[INTERVIEWER]: Also, I know there’s PBIS, how do you—

[TEACHER]: What’s PBIS?

[INTERVIEWER]: The school wide, PBIS. Positive Behavior Intervention …

[TEACHER]: Yeah, I don’t know what it is.

[INTERVIEWER]: Obviously, you don’t use it.

[TEACHER]: I don’t know what it is, in all honesty. I’ve heard that there’s a meeting on Thursdays. I think it’s tomorrow. I know there’s … Well there’s three people that’ll show up. I don’t know, sometimes I think schools do things because the district mandates them but it’s not necessarily … I don’t know what it is.”

PUNISHMENT & EXCLUSION CO-EXISTED WITH ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES

In almost all of the focal schools in our comparative case study, alternative approaches such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) or Restorative Justice (RJ) were added on to existing punitive and exclusionary measures. Thus, we observed a range of discipline practices within each school, ranging from exclusion and punishment to educative. These practices often occurred side by side or in fact worked together. This range of approaches to discipline is denoted on the School Climate and Culture Quadrants by the oblong shapes.

Below we describe the persistence of punishment and exclusion in the form of school police involvement in school matters, removal of students to continuation schools, the maintenance of in-school suspension and detention rooms, and the creation of “walkers” and “roamers” — or students who habitually roam the halls — in schools without in-school suspension rooms.

SCHOOL POLICE ACCEPTED AS NECESSARY, DESPITE EVIDENCE OF LITTLE OR NEGATIVE INTERACTIONS

School police remain a constant presence in a majority of schools.39 In 65% of the schools for which we had data, police were either stationed at school or police were readily available as backup to campus security officers. School police often parked their car in front of the school, had their own office on campus, and were described by administrators as important administrative team members. Schools without school police tended to be small charter, private independent, or rural schools. Our data suggest that the presence of school police and security officers were normalized and insinuated as necessary, despite teachers and students having negative experiences of police presence in schools.

Our data suggest that administrators have normalized police presence on campus by framing them as community partners. In all but one school in our sample, school administrators described school police as such. For example, this excerpt from field notes of an observation of a ninth grade orientation assembly held during the second week of school:

“The Dean puts up a slide with his picture and a woman and a police officer. He says this is my team. He identifies the woman as working in his office and someone who can help. He also identifies the police officer by name and says, ‘He is the school police officer, some of you might recognize him from [local middle school].’ The Dean says these people are responsible for safety and security around campus. He says we are focused on education here.”

The police are normalized as part of the school and as members of a school administrator’s team. However, when we asked administrators to describe specific instances of police involvement, many described situations in which police involvement criminalized behaviors that might have been best dealt with on non-criminal grounds. For example, students sending sexual selfies were treated as child pornography cases. In another case, a student who fell through an awning while climbing on a school building to retrieve a ball was in trouble for trespassing and destruction of property.

We found evidence that despite little evidence that school police did much more than park their police cars in the front of the school, shake hands with students, and come when called by administrators for student behaviors that cross over into law-breaking, school-police partnerships were strengthening, particularly in the Central Valley. In the Central Valley, school administrators discussed school-police grants for restorative justice, active-shooter training, police drug-sniffing dogs, and space-sharing agreements.40 In many schools in the Central Valley, administrators also discussed adding more fences and security cameras.

Moreover, we found that a RJ model derived from a victim-offender reconciliation program connected RJ to the criminal justice system in the Central Valley region. Data also suggest that this model of RJ at times involved the RJ coordinator to utilize their relationship with students for law enforcement home visits.

Federal Community Oriented Policing (COPS) grant funding has encouraged the expansion of school-police partnerships nationally, providing between $98 million and $400 million a year to hire officers during the time of this study.41 These grants included explicit preferences for school-based policing, increasing the police force in rural communities, and requiring that applicants work with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

For teachers, police presense offered a vague sense of deterrence even though they generally reported minimal interactions with school police.

“I don’t know why [the police office] is here ... not to go ahead and actually step in and work as another hallway monitor or another admin or anything like that. To my knowledge and based on what I’ve seen, it’s more of just kind of keeping it safe. You know, I fully believe that if he saw any weapon of any type that he would intervene, but I think that’s really what it comes down to.”

When they did report direct interactions, teachers often linked police to student removal from the classroom, and with the use of aggressive tactics such as handcuffs and physical force to break up fights.

“So, at the very beginning of the school year there was a really bad fight in my classroom and so the officer came in and handcuffed a student, which was kind of intense. You can only say, ‘please don’t do that’ so many times to somebody. So, I think for me, I’m still trying to understand and I want to appreciate that their job is difficult and intricate but for me it was such a ... I can’t have that in my classroom, so I’m not totally sure what their job was. I do know that in order to break up fights sometimes you need two adults to hold kids back, but I think that was such an abrasive, unnecessary level of what is needed.”

Thus, the data suggest that when asked about their first-hand experiences with school police, a majority of teachers reported only interactions limited to the kind of cursory, professional civility extended to any colleague at the school site. However, those teachers that had more direct interactions with school police almost always described incidents that involved physical force and often an escalation of conflict.

While administrators and teachers referred to a vague notion of safety as a key justification for having school police on campuses, students experienced police as conspicuously absent when students’ safety was threatened. A student, who was open to the idea of police at her school, observes how police are too busy to be concerned with “small things,” such as a student being attacked:

In another school, several Latinx students described their fear of the neighborhood around the school. They explain that they thought twice about joining after-school extracurricular activities because they did not want to walk home at night. Even though police had an office at the school site, they did not safeguard students in the walk to and from school. Instead, these same students felt threatened by their school police:

“I feel like if they were to come up to students, just the way they portray themselves, it’s going to feel like we’re already being attacked, like they’re trying to come for us just because they’re talking to us.”

A student in another school shared that the school police officer stopped him on his way to school one day because he was mistaken for someone who had just committed a crime. Thus, the presence of school police led to this student being targeted and racially profiled.

When students had direct interaction with police, they almost always described police involvement escalating to force.

“Some of the school police are cool, but it was an incident that happened last year. One of the girls was pregnant. They didn’t know the girl was pregnant, mind you, but it was a mediation, and they ended up fighting inside the art room. The school police came in, and I guess she felt like she kept antagonizing her because she kept talking back and forth to her. She was just like, ‘Be quiet. Be quiet.’ Then, she started settling down, but the girl who was pregnant was the one who got pinned up to the wall, like pushed hard against the wall. She was like, ‘I’m not doing anything.’ The other girl was trying to attack her. He wasn’t really worried about the girl that was trying to get to her. It was embarrassing, though, because it was a whole bunch of students in that hallway. Then, she got pushed hard like super hard. Her face hit the wall.”

In this incident, a fight in a classroom resulted in a police officer pushing a student hard up against the wall. The student describes the officer hitting the pregnant girl’s face against the wall, even after she had already calmed down. The student also notes the pregnant girl’s safety was most at risk, but the police failed to secure her safety and used excessive force against her.

In another incident, students explained they didn’t see the school police officer much, but once witnessed police using pepper spray to break up a fight.

Students in this focus group shared that they feel mixed about whether school police make them feel more or less safe but note the danger that police pose to bystanders.“[INTERVIEWEE 1]: That one time where they pepper-sprayed, that was one of them.

[INTERVIEWEE 5]: Well, they tried to pepper-spray, but they ended up pepper-spraying a whole group and themselves.

[INTERVIEWEE 3]: Yeah, because the kids wouldn’t stop.

[INTERVIEWER]: You don’t see police that often? Does having police on campus make you feel safe, unsafe?

[INTERVIEWEE 1]: Yeah, at some point.

[INTERVIEWEE 2]: It’s like a mixture of it.

[INTERVIEWEE 2]: You feel safe, but then it’s like, it’s to the point where you feel like you’re being held in a prison or something, because we have people who are armed, and there’s a potentiality of you being harmed because of someone else’s fault, or them pulling out their weapons because something else is going to happen. You’re just going to be a bystander, like the pepper spray … The group of people, most of them were just bystanders during the situation.”

Our data reveal that police were often absent during times when students felt threatened and that most teachers’ and students’ direct interactions with police involved the removal or physical control of students, often forcibly and aggressively. We also noted more incidents of escalating violence in schools serving some Black or Indigenous students. In at least two schools, this resulted in the removal and replacement of the school police officer. Black students in our focus group sample expressed more instances of being profiled and witnessing these experiences. This suggests that police are most often used against students, particularly Black and Indigenous students, in schools.

REMOVAL OF STUDENTS TO A COMPLEX SYSTEM OF CONTINUATION SCHOOLS

While our data on continuation schools was not as systematic as we would have liked, covering mostly continuation schools in the Central Valley and one in a rural Northern California district, it suggests that students continue to be removed to a complex system of continuation schools and other alternative education facilities.42 School enrollment data show that continuation schools across our sample disproportionately enroll Black and Indigenous students, and students describe this trend as well.

Students speak troublingly of the role continuation schools play in exclusionary practices. The following excerpt is from a focus group with members of the Black Student Union who attended a predominantly Latinx school in Southern California. Students call out the anti-Black school environment and identify the continuation school as a mechanism to continue to remove and exclude Black students:

“I say about two years ago, it was a fight between Blacks and Latinos, a big rumble … Then, when the fight ended, everybody tried to blame it on us like, ‘Oh, they’re the one who started the fight.’ They tried to kick everybody off, because we was all part of the sports team. They tried to kick all of us off, but they let the Latinos stay where they are. Half of them was the soccer team. I ain’t going to lie, the soccer team is good. They would go to the championship every year. They didn’t want to take them off the team. Then, we were like, ‘How come we got to see this punishment not the same as them?’ They tried to kick us all out. They kicked like half the Black kids out. That’s why you never see Black kids here. It’s 9% Black kids that go here and 91% Latinos.”

In addition to the school using removal to continuation schools to respond in a discriminatory manner to ‘safety’ issues like fights, the school also encouraged Black students to voluntarily re-assign themselves to continuation schools for alleged academic reasons.

School counselors and administrators created a climate of exclusion for Black students through unequal punishment and targeting for removal to continuation school.“[STUDENT 1]: They say, ‘Oh, let’s take you to [continuation school]. You can get done with school faster.’

[STUDENT 2]: Yeah. I feel like they underestimate our intelligence because I ain’t going to lie. I messed up. When I first came to [high school], my grades wasn’t up to date, and they tried to send me to a different school, and I’m like, ‘No, I got this.’ ... My counselor even told me, ‘Well, we can still send you to [continuation school].’ I don’t want to go to [continuation school] because that goes to show you like, ‘Oh, you all won the battle.’ I just want to prove a point to you all. Black kids is here. We’re intelligent students.

[STUDENT 3]: It’s basically like they don’t want to deal with us at this school.”

In the Central Valley, we found that schools actively removed students to a complex system of alternative education facilities regardless of TCE involvement or alternative discipline approach adopted. Reasons for removing students to continuation schools included improving graduation rates, removing special education students who were disruptive in class, and removing students considered to be gang members. The mission of one district’s continuation school found on their website stated an unusually candid explanation of their mission:

“The mission of our school is to address the needs of the specific student population who chronically experience attendance and discipline problems as well as lower achievement levels. The existence of this school site additionally provides a valuable service to other school settings by eliminating the students who would potentially raise the suspension and truancy rates.”