︎︎︎ Full Report (PDF)

︎︎︎ Executive Summary (PDF)

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

2. Summary of Findings

3. Summary of Recommendations

4. LESSONS LEARNED

5. Uneven Institutionalization of Alternative Approaches

a) The Persistence of Punishment and Exclusion

b) Deepened School-Police Department Partnerships

c) Growth of Criminal Justice Models of Restorative justice Risk expanding carceral logics in schools

d) Removal of Students to a Complex System of Alternative Education Facilities

e) Creation or Re-Creation of In-School Detention and Suspension Rooms

f) Use of Alternative Approaches for Maintaining Orderly Hallways Despite Chaotic or Intellectually-Deadening Classrooms

g) The Expanded Role for Assistant Principals — An Unexpected Institutional Impact

6. Institutional Supports

a) Teachers Express Diverse Perspectives on School Discipline

b) Educator Preparation and Training Programs, Particularly University-Based

c) Flat District Organizational Structure

d) Leadership with Capacity-Orientation Toward Adults and Students

e) Organizational Structures for Adult Collaboration and Learning

7. Remaining Institutional Obstacles

a) Policy Pressures Created Top-Down Constructions of the Problem and Solutions

b) Insufficient Resources for Supporting Positive and Supportive Classroom Practice

c) Trainings that Hold Deficit Orientations Toward Adults

8. Conclusion

9. Appendices

10. Endnotes

Suspension Decline in California's Heartland: A Central Valley Story

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Stretching 18,000 square miles, the Central Valley is one of the most productive agricultural regions globally and one of the fastest-growing regions in the state by population.1 Yet, this is a region of enormous contrasts. For example, although the Central Valley produces more than $50 billion of income per year, it remains one of the country’s poorest regions — poorer even than Appalachia — because so much of its wealth is extracted. The region’s lack of significant political clout in Sacramento, low philanthropic investment, high unemployment rate, and low educational attainment often overshadow its assets. The perception that the region is more socially conservative than most other parts of California can also mask the progressive advocacy and cutting-edge innovation occurring there. The Central Valley’s political and economic conditions reflect much of America. Along with its rich multicultural and multinational history and its current racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity, the Central Valley can serve as a model for other communities. The Central Valley represents the heartland and future of California.

Educational policy and practice in the Central Valley offer insights into the current pulse and potential directions. Numerous Central Valley school districts adopted new district and school policies, and piloted alternatives to suspensions and expulsions in the past decade. They did so in response to shrinking law enforcement budgets during the Great Recession that spurred juvenile justice reforms and growing recognition that zero-tolerance discipline policies led to high suspension and expulsion rates, more unsupervised students on the streets, negative social and academic outcomes, and criminalization of students.

The California Endowment (TCE) acted as a core funder and convener of many efforts to challenge punitive and exclusionary school discipline across the state. In the Central Valley, The California Endowment engaged in a regionally defined approach with five specific strategies:

-

TCE solicited proposals from school districts in the region and funded 12 districts to engage in new or continuing positive school discipline efforts and participate in a Leadership and Learning Network

-

TCE encouraged educators to explore restorative justice (RJ) practices and funded school-level change efforts as part of TCE’s Building Healthy Communities (BHC) place-based initiative.

-

TCE funded district-led initiatives to explore and implement either Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) or restorative justice practices (RJ) across the district.

-

TCE funded community-based advocacy organizations in some areas of the Valley that organized to pass local school policies.

-

TCE engaged in state-level policy advocacy, which contributed to the passage of positive school discipline legislation.

Additionally, the Endowment funded a five-year developmental evaluation of their efforts. The interdisciplinary research team brought together lawyers, educators, and researchers from the Central Valley and outside. Unlike traditional evaluations that are summative and often engender feelings of external accountability, developmental evaluations embed researchers within a work team to provide context-specific knowledge and lessons that inform future philanthropic strategies and enable continuous cycles of learning and action for the work team.2

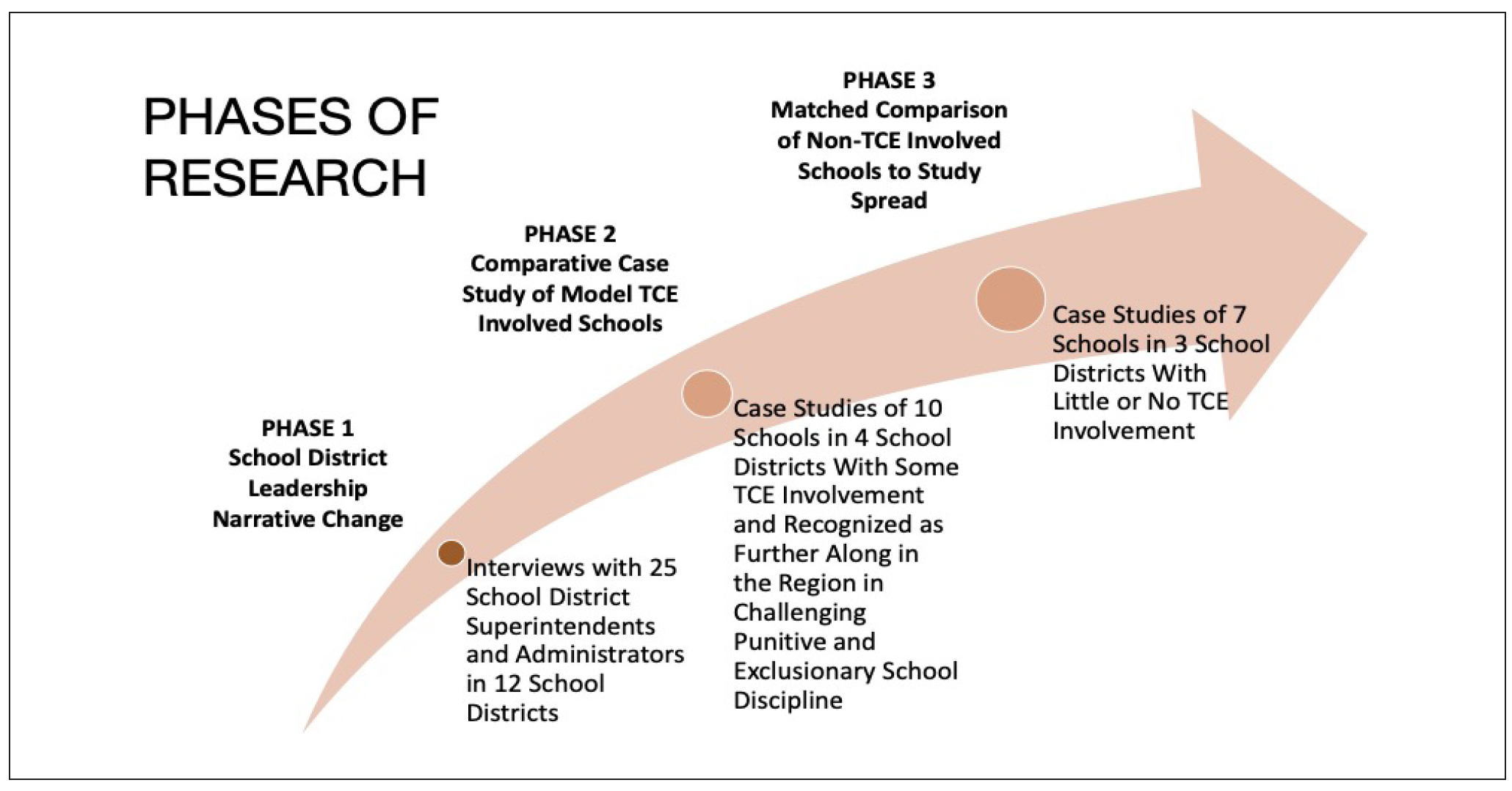

The five-year project began by examining narrative change among district administrators in 12 districts in the region. Subsequently, in Phase 2 of the study, the developmental evaluation selected four school districts in the region with schools that district leaders and program managers had identified as having made significant headway into implementing alternative school discipline systems. The first goal was to study the extent of school culture change in schools with reputations of being further along. The second goal was to identify successful strategies and persisting obstacles to challenging punitive and exclusionary school discipline in these schools.

In Phase 3 of the Central Valley School Discipline Learning Project, the research team examined two important aspects of The Endowment’s theory of change regarding systems change — the concept of spread and institutionalization.

We define spread as the process by which changes in narrative, policy, or practice seeded in particular locales due to organizing, advocacy, or resource allocation encourage changes or ripple effects in other places. To study spread, we expanded our case study sample to include schools not funded or otherwise involved with TCE that had similar size and student demographics to those we had previously studied.

When changes are seeded, exploring how they take root and influence school life contributes to our understanding of the durability of school change. Institutionalization refers to how an organization incorporates changes in narrative, policy, or practices into the day-to-day functioning through new roles, job descriptions, routines, procedures, forms, and allocations of scarce resources like money, space, and time. To study institutionalization, we closely analyzed teacher interviews and observation data.

In this report, we answer the following questions:

| 1.

Have non-punitive or non-exclusionary school discipline practices spread to school districts in the Central Valley not directly funded by The California Endowment? If so, how? | 2.

In what ways have supportive or positive school discipline practices become institutionalized in schools in the region? |

3.

What are the sources of support and obstacles for educators in the Central Valley to challenge punitive and exclusionary school discipline practices? |

Back to top ↑

2. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

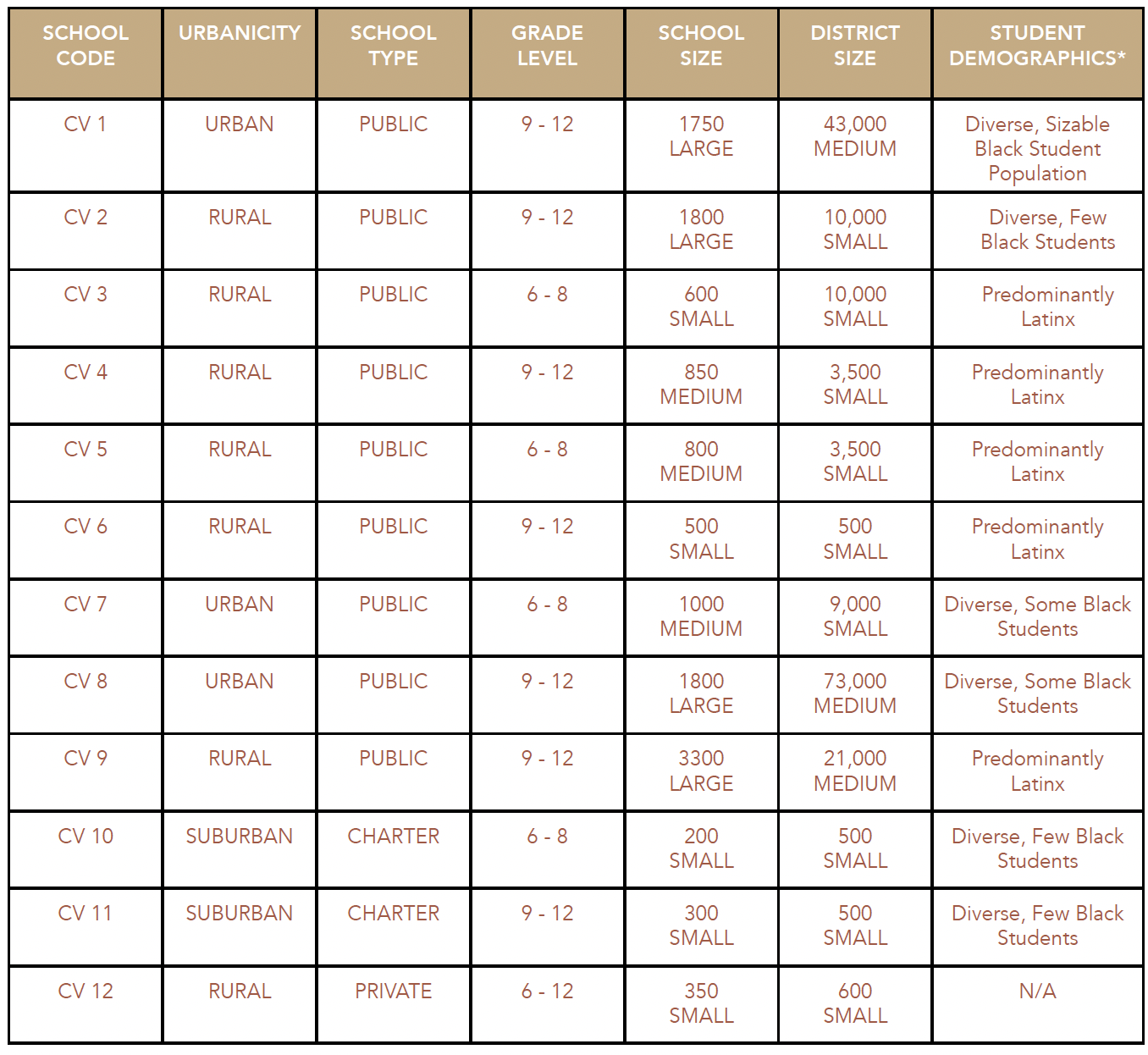

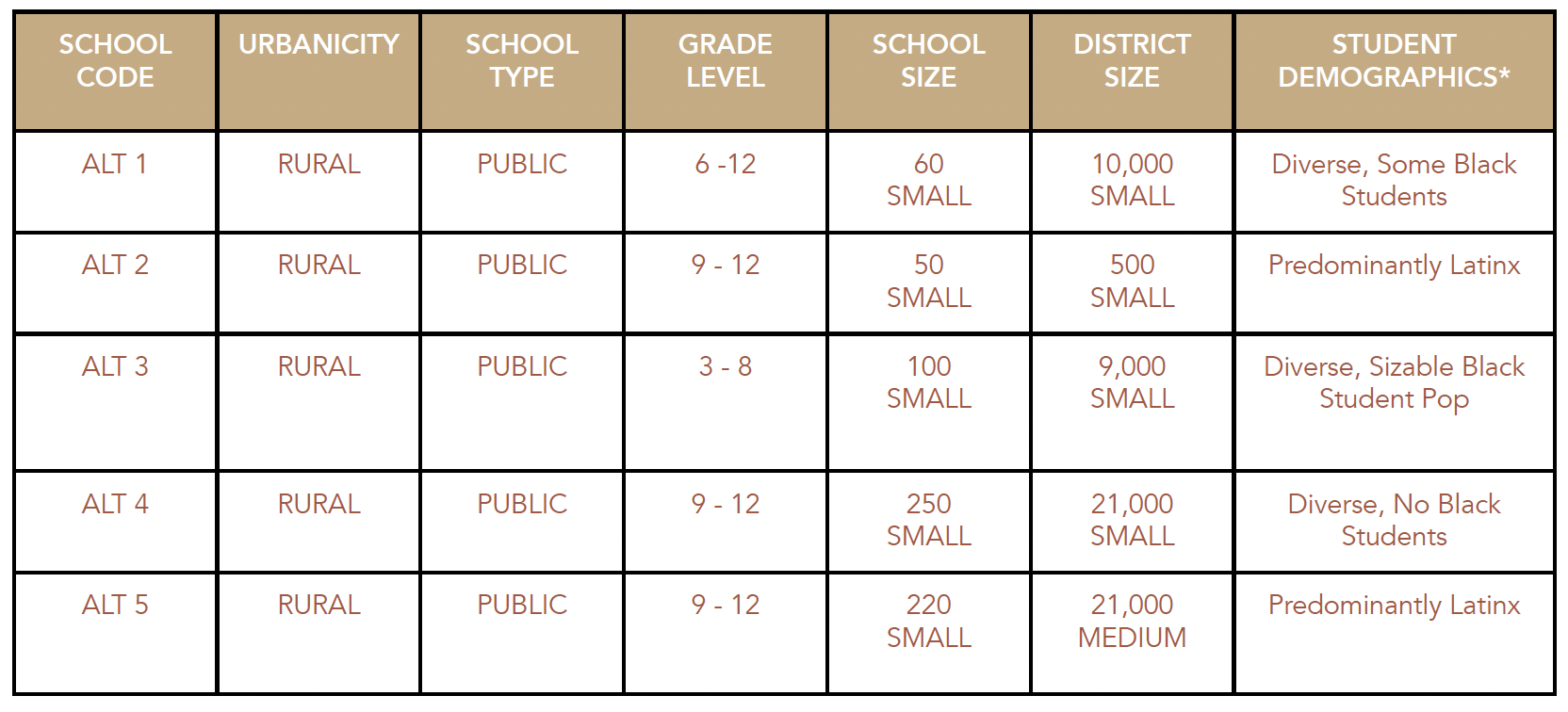

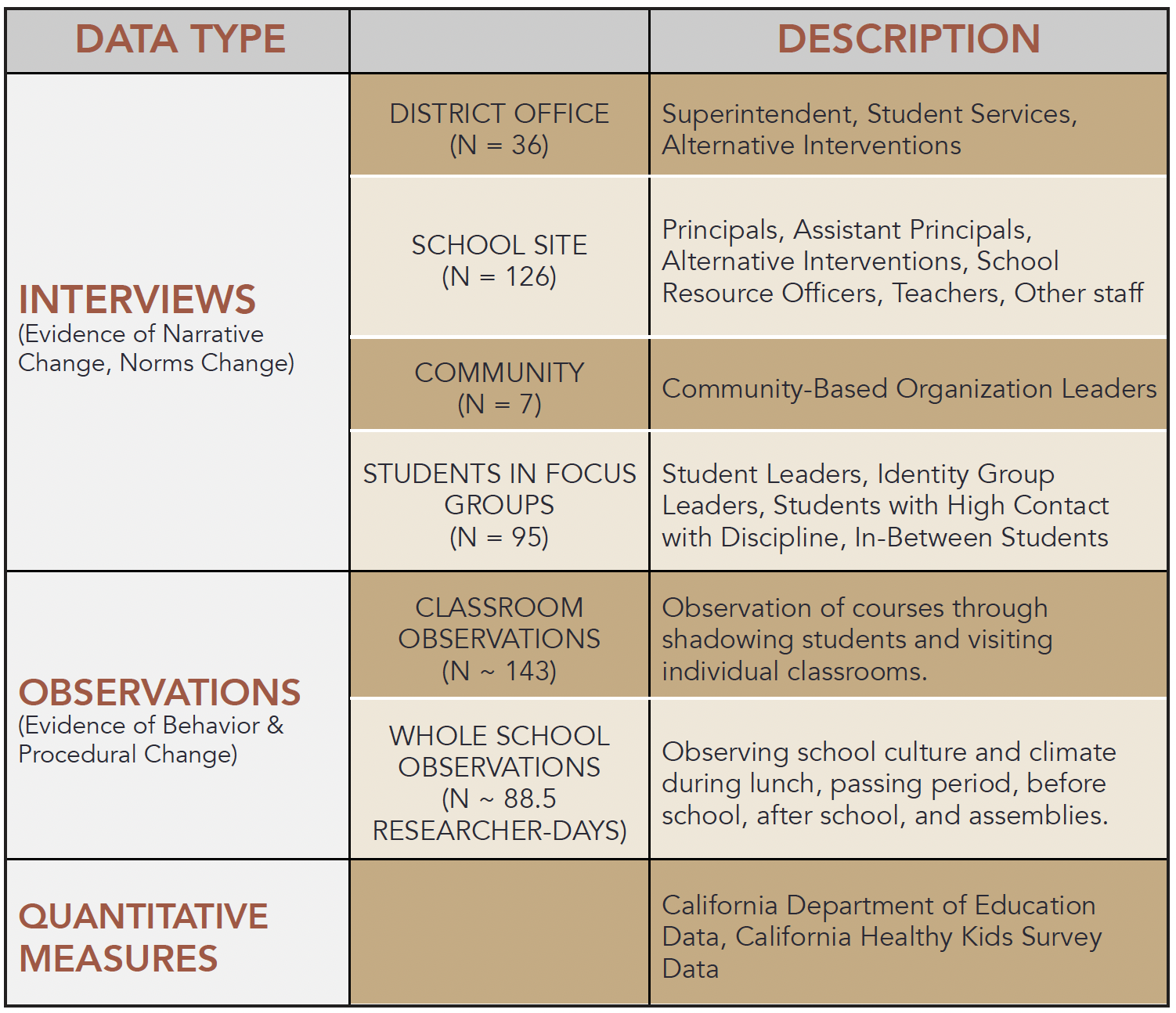

The interdisciplinary research team conducted a qualitative comparative case study of 12 comprehensive secondary schools and 5 continuation or alternative schools in 7 school districts. The research team collected and analyzed 36 interviews of district office administrators; 126 interviews of school personnel; interviews with approximately 95 students in focus groups; observations of 143 individual class periods; and observations of passing periods, lunch, and other regular school activities for a total of 87.5 researcher-days. Additionally, the research team analyzed suspension data available from the California Department of Education.

Question 1:

Have non-punitive/non-exclusionary school discipline practices spread to school districts in the Central Valley not directly funded by The California Endowment? If so, how?

Central Valley schools within and outside of the TCE’s Building Healthy Communities (BHC) place-based initiative succeeded in reducing suspension rates overall. The timing of the most significant drops in suspensions occurred between the academic year (AY) 2011–2012 and AY 2012–2013, which preceded the implementation of systematic alternatives to suspensions in all but one school in the sample. Thus, declines in suspensions in this region may be better explained as school-level responses to state and federal data collection on suspensions that began during this time. However, data suggest that schools continued to experience varying degrees of district central office pressure to reduce suspensions leading every school in our sample to experiment with alternative approaches to discipline such as restorative justice and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports.

While community-based organizing and advocacy by groups partially funded by TCE resulted in state policy change, district policy adoptions in two districts, and a successful legal challenge in another3, there was less evidence that educators felt direct pressure or support from community-based organizations or advocacy groups. It’s important to note that in this region, we found that when school leaders spoke of community partners, they named police departments, sheriff departments, local agribusiness, social service agencies, and churches instead. See pp. 13.

We found that local educator preparation programs such as Ron and Roxanne Claassens’ Discipline that Restores provided significant theoretical and practical support to many restorative justice educators in the region.

Question 2:

How have supportive or positive school discipline practices become institutionalized in schools in the region?

Overwhelmingly, the research team experienced schools in this region to be calm and safe. Yet, punishment and exclusion were still present in every school. Despite declines in suspensions and universal adoption of alternative approaches to discipline such as PBIS and RJ, schools continue to send students to a complex system of continuation schools, and most schools actively use in-school suspension rooms to warehouse students during the day. While some PBIS and restorative justice practices have been institutionalized, in most schools with limited resources, these practices have been narrowed towards social control purposes, such as eliciting apologies, rather than community-building purposes.

School-police partnerships are deepening in the region, partially encouraged by increased federal grants from the Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS). These grants prioritize the expansion of school policing in rural regions and make working with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) mandatory.

The most common justification for surveillance, punishment, and exclusion, particularly of Latinx students, was perceived gang affiliation. Those educators that discuss “gangs” in the region appear to evoke the idea to describe a conversation-ending external threat — the justification for removal or exclusion that required no additional explanation. There was little recognition of root causes or holistic responses to gang-involvement.

Supplemental and sustained funding is necessary for institutionalization. In schools that did not receive any additional funding to create alternatives to punishment, administrators often resorted to superficial responses to reduce suspensions that simply and temporarily removed students to new locations in the school. In schools that received additional funding to implement alternative approaches, we found some initial signs of institutionalization, but sustained funding is necessary for deeper and lasting change.

In this region, a new model of Restorative justice (RJ) derived from criminal justice may lead to troublesome school-police partnerships that increase the criminalization of students. Schools in the region that implemented criminal justice-derived models of RJ utilized mediation circles to reach agreements for restitution of harms against the school (e.g., vandalism, pranks, threats). We found this model of RJ encouraged educators and youth development workers to describe students as cases, mistakes as offenses, and to engage in police activities.

Question 3:

What are the sources of support and obstacles for educators in the Central Valley to challenge punitive and exclusionary school discipline practices?

The traditional role of assistant principals has grown and can be an important lever for change. Rather than just responding to crises and office disciplinary referrals, Assistant Principals are responsible for identifying new approaches to improve the overall school climate and culture. These changes in the traditional role of assistant principals are important to note because the professional pipeline of who can and should lead these efforts and the training and structural supports required to do this work well are potential places to invest resources.

Despite often hearing from administrators that teacher resistance obstructed progress, we found that a vast majority of teachers expressed support for educative and/or restorative reforms to school discipline. Teachers expressed support for non-punitive approaches to discipline, but voiced frustration with the motivations and implementation of these approaches. We also found that training in alternative discipline approaches that assumed a deficit-orientation towards educators, created pervasive negative experiences.

Teachers in our study held both asset- and deficit-oriented narratives of students, parents, and communities, with adults holding primarily deficit-oriented narratives comprising a minority of our sample. These patterns suggest that additional educator pathways to recruit, prepare, and support teachers from the same cultural, racial, and socio-economic background as the majority of students in the region are important. Furthermore, these findings suggest that attention to the preparation and ongoing support for non-punitive disciplinary practices and humanizing and critical pedagogies for all teachers in the region is necessary.

In the region, many of the leaders and teachers of restorative justice (RJ) were trained through in-depth programs, often housed in undergraduate or graduate university programs. In particular, Fresno Pacific University (FPU) appeared to have supported the preparation of the school administrator or teacher practicing Restorative justice in five of the seven comprehensive schools practicing RJ in the region. These educators demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of the values behind Restorative justice and the technical aspects of the practice.

Flat district organizational structures in the small and medium-sized Central Valley districts allowed for more resources, decision making, and leadership at the school site, which fostered ownership, experimentation, and tailored implementation. Schools with the most vibrant and supportive school climates also had collaborative teacher cultures supported by common planning times, collaborative teams, site-initiated professional learning, and democratically shared data.

Back to top ↑

3. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

- Beyond lowering suspension numbers, invest in sustained efforts to use Restorative justice practices to build community, student leadership and activities, alternatives to punishment, and engaging curricula.4 Ongoing training, release time, teacher collaboration, and school visits are essential to institutionalizing new practices.

-

Implement restorative practices in restorative ways. Approach educators with the perspective that they are capable of reflection, learning, and growth. Ask them what they have experienced, what they want, and how they may be best supported to improve their craft.

-

Discontinue punitive structures and practices. Maintaining in-school suspension rooms where students complete reflection sheets but fall further behind in class perpetuates the same harm under a different guise. Preserving punitive structures allows the practices to continue. Discontinuing these structures creates the need to build alternatives.

-

Resist adoption of criminal justice derived models of Restorative justice and school-police partnerships. Enlarging partnerships between criminal justice and education tends to increase law enforcement approaches in educational settings. Instead, strengthen educative approaches that focus on community building and strengthening students’ capacities to critique, transform, and heal their world.

-

Create new professional pathways, preparation, and support for Assistant Principals. Invest in educator preparation programs that recruit and develop teachers and leaders with asset-oriented views of students and families, teach restorative justice, and foster transformative and collaborative leadership models.

-

Re-examine assumptions regarding “gang-affiliation” or “gang-involvement” when it is used to justify punishment, exclusion, and surveillance. Build understanding about the root causes of gang involvement

Appreciations

We would like to thank the many young people, parents, leaders of community-based organizations, teachers, school staff, principals, and school district administrators who generously shared their time and insights with us. We would also like to thank The California Endowment staff — Annalisa Robles, Brian Mimura, Castle Redmond, Jennifer Chheang, Mona Jhawar, Sabina González-Eraña, and Sarah Reyes — who co-designed this study with our team and engaged reflectively in the research and learning process.

Back to top ↑

4. LESSONS LEARNED

Have non-punitive and non-exclusionary school discipline practices spread to school districts in the central valley not directly funded by The California Endowment (TCE)?

If so, how?

We found similar evidence of narrative change related to suspensions, adoption of alternative discipline approaches, and overall reduction of suspensions in schools not directly funded by The California Endowment as those directly funded by TCE. Evidence suggests that there were multiple sources of pressures and supports for these changes; primarily ones being state data collection, varying degrees of district central office pressure to reduce suspensions, and the presence and access to high-quality training for alternative approaches, especially from university programs.

In this region, both within and outside of the BHC, there was little evidence that pressure or partnership with community-based organizations or advocacy organizations influenced school-level efforts. In one exception, an educator explains that despite being aware of the organizing efforts to remove police from schools, they felt that the police officer stationed at their school could relate well with students. In contrast, school administrators in the region most commonly mention community partnerships with local law enforcement — either police or sheriff’s departments, a finding we examine in more depth below. However, the opportunity to visit other schools or to have other schools visit theirs was an important motivator for initiating and sustaining efforts.

We found that in schools not directly funded by TCE, administrators share similar narratives to those directly funded by TCE. They report suspensions are ineffective in improving student behavior and note the importance of adopting positive or restorative alternatives to school discipline. A school administrator recalls a conversation with a peer who shares their frustration with earlier zero-tolerance policies:

“He asked me, ‘Do you ever feel like all you do is suspend kids all day? Like we help them, we support them, but yet … then we still have to send them home.’ There’s something that’s not right about this. I didn’t choose this profession to do this all day.”

This is a common refrain in the region.

Administrators often note suspending students is not really punishment since students likely just play video games at home. They also share that suspensions result in a loss of instructional time and students who return to school further behind.

This evidence suggests that narratives about the effectiveness of suspensions has shifted for schools in the Central Valley but administrators’ concerns about school discipline remain primarily focused on finding the best tool for changing student behavior to comport with adult expectations and on maximizing instructional time and attendance.

In examining suspension data we found that narrative change largely corresponded with actual changes in overall use of suspensions for all schools in our sample. Suspension rates, calculated as unduplicated counts of students suspended divided by the total enrollment, has decreased over time among schools within the Building Healthy Communities school districts, among schools involved with TCE only through the regional Leadership and Learning Network grants strategy, and among schools with no direct involvement with TCE (see Figure 1).

What led to the decline in suspensions?

While administrators ascribe the impetus to reduce suspensions to their personal realizations that suspensions were not working to promote more desired behaviors, the most prominent drops in suspensions between the 2011–12 and 2012–13 academic school years, preceded implementation of systematic alternatives to suspensions in all but one school in the sample. Thus, declines in suspensions are better explained as school level responses to state and federal data collection on suspensions. California’s collection of school discipline data began in the 2011–12 academic school year, following the collection for the first time of federal suspension and expulsion data collection in the 2009–10 by the Department of Education’s civil rights division.

From our qualitative data, there is evidence that school administrators simply did not suspend students for being tardy, missing detention, or otherwise breaking minor school rules, which led to the initial decline in suspensions. In one secondary school with some of the highest suspension rates in the Central Valley region, a school administrator explains they had nearly 1,200 suspensions in the 2009–10 because they followed a school policy in which students were given Saturday school for being late — and if a student did not show up for Saturday school, they were suspended.

The school dropped their suspensions to less than 900 in the following year, immediately after ending this practice, and to nearly 200 suspensions the next year.

In most schools in our sample, school leaders and teachers reported pressure from the district central office to reduce suspensions. As an example, one school administrator explains:

“Three months ago we were the highest school for suspensions. And everybody was reducing by 50 and 75 percent. We were told that we have to reduce our suspension rate by 35 percent. And that’s a goal that we can shoot for.”

We found a general trend that in schools without sizable grants from either TCE or another source to try out alternative discipline approaches, district pressures to reduce suspensions often corresponded to more superficial school responses including in-school suspension rooms. These findings are described in more detail in Section II.

Thus, this data suggests that federal and state policy shifts away from suspensions, and the inclusion of suspension and expulsion data into accountability dashboards, is a significant driver for the early and dramatic declines in suspensions in the region.

We found that schools in our sample, whether within or outside of BHC, adopt a similar range of alternatives such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and restorative justice (RJ). We found that schools chose particular approaches generally by happenstance. Within non-BHC schools in our sample, school leaders tend to adopt interventions that they come across, either through their own professional preparation, e-mailed training notices, or through County Office of Education offerings. In particular, the adoption of PBIS in the region appeared to be heavily influenced by the Special Education Local Plan Area (SELPA) of Fresno County Office of Education’s PBIS implementation initiative, which began in 2010-2011 and trained more than 1,200 adults by May 2013.5 Restorative justice training in the region was primarily influenced by the Fresno Pacific University’s Center for Peacemaking and Conflict Studies and the translation of many of the principles to schools in Discipline that Restores.

The Fresno Pacific University’s (FPU) Center for Peacemaking and Conflict Studies primarily influenced restorative justice in the region and the translation of many restorative principles to schools in Discipline that Restores. Several school leaders in our school sample studied at FPU’s teacher or leadership preparation programs. Secondarily, staff from two of the schools in our sample were trained by Restorative justice for Oakland Youth (RJOY).

Within the focal schools in this region, whether within or outside the BHC, there was little evidence that pressure from community-based organizations or advocacy groups was a significant driver for changes to school discipline. It’s important to note that in this region, we found that when school leaders mention community partners, police departments or sheriff departments, local agribusiness, social service agencies, and churches are most often named.

While we found declines in suspensions and universal adoption of alternative approaches to discipline, such as PBIS and RJ, our data suggests that positive and supportive school climates and cultures are still far from a reality for a vast majority of students in the region. Punishment and exclusion are still very much present in most of the schools in our study, primarily in the five ways we describe more fully in Section II.

Back to top ↑

5. UNEVEN INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES

In what ways have supportive or positive school discipline practices become institutionalized in schools in the region?

In every focal comprehensive school in the region, school climate and culture is a central concern, and school leaders expressed that they are or were in the process of implementing Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) (45% of schools), restorative justice (RJ) or restorative practices (64% of schools), or Character Education (18% of schools). Some schools implemented more than one intervention. For example, one school adopted a combination of PBIS and RJ, and in another we observed a combination of PBIS, Character Education, and conflict mediation.

Within our limited case studies in the region, it did not appear that adopting multiple alternative approaches was better than only adopting one. In the first school, RJ is relegated to harm circles, limiting the use and impact of the approach to Tier 3 responses in the PBIS framework. In the second school, the mixture of approaches resulted in limited observation of any of the approaches becoming institutionalized.

We found that some aspects of alternative approaches to discipline have become more institutionalized than others in the focal schools in the region. For example, PBIS practices such as school climate and culture teams, reward or award assemblies, and large, vinyl posters of positive school expectations tailored to different locations within the school have become commonplace and sustained within schools that have adopted PBIS in the region. In contrast, other aspects of PBIS, such as PBIS rewards or “bucks”, have not become institutionalized in a majority of schools employing PBIS. We only found evidence of educators rewarding good behavior with bucks or other rewards in one of the 17 schools in the study.

Absent sizable resources for sustained training, and modeling, we found that RJ struggles to become institutionalized within existing school systems. We have some evidence of institutionalization of restorative practices into everyday practices and routines, including a requirement that students to complete reflection sheets when removed from class. On these sheets, students are expected to reflect upon what they have done wrong, offer an apology, or plan to changing their behavior. We found this practice somewhat routinely used in most of the schools that adopted the RJ approach. In this limited way, RJ attempts to provide context for understanding student behaviors and the opportunity for students to reflect and learn from conflicts has created a more educative approach to discipline.

The most significant impacts we’ve seen is in youth leadership development associated with RJ peer mentors, and in self-reported shifts in understanding and relationships with students that educators who have participated in RJ circles have shared with the research team. While practiced differently in different settings, Restorative justice circles are facilitated discussions held in a circle to build community, understanding, empathy, and collective problem-solving. Participants take turns sharing their stories, experiences, and thoughts in response to prepared prompts, such as, “Who has helped you become who you are,” “How were you impacted by what happened,” “How did it make you feel,” and “What could you do to make it better?”

Adults speak to the “restorative elements” that emphasize relationship building between adults and young people at one school.

Here a staff member speaks to the “relational piece” that leads to a culture of understanding between teachers and students, and makes space for more educative, less punitive responses to student behavior.

“The difference? I think it’s so much more positive, and it’s so much more focused on how to understand one another and understanding that we make bad decisions, but that’s okay. And I think in working with my students that do make mistakes, I try to do three things with them. I try to go back and say to them, what was the decision that you made? Why did you make that decision? And okay now because of that decision, these are the things that have happened. You’ve hurt a relationship with friends or you … Is that relationship still important to you? If it is, then we need to talk. We need to have a mediation time … And try to build understanding that everybody does things differently, but it’s more learning to tolerate and understand each other.”

Thus, RJ approaches appear to live on in individual teachers’ and administrators’ interaction with students. However, educators explain that to do RJ well requires a great deal of time for preparation, pre-conferencing, holding a circle, debriefing, and following up. Without additional resources, teachers and administrators lack this time — we found that even where there is considerable commitment and expertise, the loss of funding for a particular program or position often means the end of RJ practices in the school.

We describe these supports and constraints, in addition to their impact on institutionalizing alternatives to punishment in more detail in Section III.

THE PERSISTENCE OF PUNISHMENT AND EXCLUSION

We found that despite the declines in suspensions and the attempts to build non-punitive school climate and cultures through the adoption of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) or restorative justice (RJ), schools within and outside of Building Healthy Communities (BHC) continue to practice a considerable amount of punishment and exclusion. We found evidence of deepened school-police partnerships, complex systems of alternative education facilities, creation or re-creation of in-school suspension rooms, narrowed alternative approaches to school discipline to conform student behavior to dominant adult expectations, and increased acceptance that empty quiet hallways signal good schools — despite the sometimes chaotic and frequently deadening classroom cultures and climates that lay hidden behind closed doors — in the region.

While these trends existed in all of the focal school districts we studied, they appeared more severe in school districts that did not receive additional funding through TCE or other grant sources in the region to create more systematic alternatives. In these schools, administrators without additional resources to shift classroom practices often resort to superficial responses to reduce suspensions that temporarily removed students to new locations in the school and returned students to classrooms where little teaching and learning were taking place.

DEEPENED SCHOOL-POLICE DEPARTMENT PARTNERSHIPS

School-police partnerships are strong and growing in the focal schools of our study, regardless of TCE involvement, suggesting that these aspects of the school-to-prison pipeline or school-prison nexus are strengthening, not weakening in the region. 73% of the focal comprehensive schools in our study have a police officer stationed at the school. In a vast majority of these schools, the police officer has their own office on campus, parks a police car visibly on school grounds, and is described by administrators as an important partner in sustaining a safe school climate. The only schools within our sample without a police officer on campus are a charter school, an independent school, and a small rural school.

Furthermore, school-police partnerships in the focal schools appeared to be strengthening. For example, one school administrator shares that they recently participated in active shooter training and describes plans to build stronger fences and install new surveillance cameras. Beyond providing police offices on most school campuses, we found growing evidence of school facility sharing with local law enforcement in the focal schools in this region. A newly built state-of-the-art community building is primarily used by staff for meetings and by local law enforcement for training on one school campus. An administrator leading RJ implementation in another school shares that the school planned to house a police substation on campus since the school had ample space and increased traffic in the area. In yet another school, where we found broad commitment to RJ and deepening implementation, the superintendent proudly shares her pursuit of a new grant with the County Sheriff’s Office.

This trend in the region builds upon three interrelated phenomena. First, school leaders shared a common narrative that police departments and County Sheriff’s Offices were important partners to their self-conceived role as school administrators.

Second, data suggest that the availability of federal grant funding encourages the expansion of school-police department partnerships. For example, the Department of Justice Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) grants created competitive grants that provided between $98 million and $400 million a year nationally to hire officers during the time of this study.6 These grants, many of which were awarded to the Central Valley region, include explicit preferences for school-based policing, increased police forces in rural communities, and requirements that applicants work with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Third, we found that across hundreds of interviews in the region, teachers’ feelings of safety and fears of school shootings justified the need for school police presence, despite a paucity of evidence of any actual engagement with them.

This trend of deepened school-police department partnerships in the region stands in contrast to the evidence of their utility in schools. We found that, in most schools, police did very little — researchers, teachers, and students mostly noted their presence by, ‘their car parked out front’ and some handshaking with students.

At one school, which is an exception, administrators describe problematic behavior to be largely cellphone use, tardiness, and ball-throwing in the hallways, where police and drug-sniffing dogs were brought in several times a year. Additionally, evidence suggests that police escalate encounters with students in the few instances where police become involved. In one instance, a student’s sexual selfies were treated as child pornography. In another, a special education student attempting to jump the school fence to return to school escalated into charges for assault on a police officer.

The trend is further facilitated by a model of restorative justice derived from criminal justice, which creates a more seamless continuum between schools and the carceral system in the region.

GROWTH OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE MODELS OF RESTORATIVE JUSTICE RISK EXPANDING CARCERAL LOGICS IN SCHOOLS

Particular to this region, we found a close nexus between restorative justice (RJ) and policing, which derive from religiously affiliated victim-perpetrator reconciliation programs that provide alternatives to incarceration.

While these programs may well provide important decriminalization pathways in the criminal justice system, the data in this study suggest that the growing partnerships between schools and police arising from this model of restorative justice may strengthen, rather than challenge, the school-prison nexus, or what others describe as the youth control complex, in this region.7 In this nexus/complex/system, multiple institutions — both the punishing and nurturing arm of the state — work together to identify, criminalize, and stigmatize youth, particularly young men of color.

We learned that in one school district well-known in the region for implementing RJ as an alternative to incarceration, RJ in schools began during the Great Recession when local police budgets decreased, and local church and neighborhood watch organizations raised concerns about young people roaming the streets after being expelled from school. A school RJ restorative justice coordinator explains:

A school RJ coordinator explains,

“At the time we were expelling kids, we were expelling quite a bit of kids. Where were the kids at now? They were out on the streets. At the same time when the [Church] Neighborhood Watch people were walking around, they saw this. So, we had to create a partnership with the school. We had to create a partnership with the police because we were providing police all this work. And that’s how everything kind of came into place. And then the [Church] just provided that process.”

The RJ model that this school district implements focuses on restitution, especially for transgressions toward the school like vandalism, threats or pranks, and the like. This RJ approach does not focus on practices often associated with other models of RJ, such as community building, challenging hierarchies or divisions through circle conversations, or building deeper understanding between teachers and students.

The criminal justice-derived RJ practice in this district, an exemplar for the region, emphasizes close working relationships between the RJ coordinator, school administrators, social workers, and police:

“So, we’ll dialogue. We’ll talk, and it’s ‘Hey, what do you got for me?’ sometimes I’ll say…’Hey, got any cases?’ — that type of a thing, to ‘What’s going on, what kind of situations have you been dealing with,’ ‘What can I help you with,’ ‘Can I take anything off your plate that is very low level that you think can be beneficial?’… I stand out there and maybe there’s not a lot of student interaction all the time, but I’m rubbing shoulders with our learning directors, principals, social workers, and our police officer who’s usually out there too.”

In another school in the same district, an RJ coordinator explains that cases are referred by police or school administrators, depending on where the “offense” occurs. Then, through a victim panel, the perpetrator hears from the victims how their conduct impacted them, and the RJ coordinator helps the perpetrator and victims determine restitution. In the case of a student who trespassed on school grounds during a holiday to retrieve a ball and fell through an awning, creating close to $1000 in damage, the grandparents of the student repaid the cost of the damage and the student was assigned 20 or 30 hours of community service. Through this incident the student learned about the impact of his actions on the schools as well as his family, repaid the school, and even gained a job after completing his community service.

In this way, RJ coordinators describe RJ as a way for a small community to work together to care for itself. At the same time, one RJ coordinator’s description of how they work with police suggests that they utilize their knowledge of and relationships with students and families for out-of-school police activities:

“So [Officer] and I will kind of case by case, situation by situation, he’ll come to me and be like, ‘Hey, I might have a case for you. Here’s kind of the parameters of it. What do you think? If it ends up coming your way as kind of the option. Would you be open to that?’ or ‘Hey, can you come with me and can you come talk to this kid with me?’ … [I]n that particular [home visit] that student had made threats to school indirectly and that student had been somebody that I had spent a lot of time with, kind of trying to mentor and keep out from doing something like that. We had just opened a case in relation to racial bullying with that student. And so, there was some rapport that I had with that student that PD [Police Department] wanted to have in the room as well. So, in that particular one, there was SRO [School Resource Officer] just needing to talk to family and I was there because I probably spent the most time out of all those people with the student … I was there not to work per se but I was there to be that relational piece for the family, for that student. So, I’ve done some of that. The latest situation is just a kid demonstrating a lot of gang signs. Like early signs, colors, behaviors, all that sort of thing.”

This approach to RJ risks redefining students as cases and potentially enlists youth development workers and school personnel into police work. While this model of RJ expands RJ practices within the criminal justice system and reduces criminalization, its expansion within schools risks expanding criminal justice assumptions and processes further into schools.

REMOVAL OF STUDENTS TO A COMPLEX SYSTEM OF ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION FACILITIES

Consistent with earlier findings, we found that schools actively remove students to a complex system of alternative education facilities in all of the focal school districts in the region, regardless of TCE involvement or alternative discipline approach adoption.

These facilities in the region range from independent studies programs to continuation schools, charter continuation programs, and partial lockdown facilities. In most districts, these facilities act as locations to warehouse students deemed ineducable in increasingly prison-like conditions. These facilities are often heavily gated with little or no green space and classroom activities that involve completing packets with little or no group instruction or socializing.

In contrast, in one school district we visited in the region, we found smaller learning environments, stronger teacher relationships, and engaging curricular and extracurricular activities in two of their three alternative facilities, specifically the independent study and continuation schools. Still, their third alternative education facility is described as a partial lockdown facility where students with behavioral issues are sent. Leadership in these alternative facilities ranges from leaders who see their role as providing important second chances for students for whom comprehensive schools do not work, to leaders who were dumped and discarded by the district to lead schools primarily to recover Average Daily Attendance monies for the district.

The pressure to remove students to alternative schools in the region is a result of accountability pressure and desire to be rid of disruptive students, particularly special education students. In one school outside of BHC that experienced a great deal of district central office pressure to improve behavioral and academic measures without any additional funds, a teacher explains the pervasive use of exclusion and removal to alternative education.

A special education teacher explains:

“According to our dashboard, when you look at our English scores, it’s green, it’s good. You look at our math scores, it’s good. It’s green. And you look at our graduation rate. It’s like at 84%. So, that’s not good. So, if you move the students out before they graduate to some other school, then it doesn’t affect our dashboard … So, as a special ed teacher, I’ve already shipped out, I want to say by the end of the semester already shipped out five kids on my caseload that, they were seniors, they had 75 credits. One had 110. Another one had like, 80, they were all close to 100. And they were all shipped out.”

In another school, a special education teacher explains the use of exclusion to alternative education as a means of ridding the school of students who disrupt their classrooms:

“The other two kids that were SPED [special education], the ones that were in the peanut gallery, heckling and making more problems, every teacher was like ‘I’m so glad that they’re going to get out of here. They have just ripped our classes apart.’ And we have, it’s to the point where it’s like, ‘thank God something is going to push them out.’ And I know that feeling as a teacher, one or two kids that are just taking away from the learning of everybody else. And so, you do feel grateful at times when it’s like, okay they need another setting. We’re not helping them by being here either.”

In this case, the teacher describes the benefits of removing two students for “heckling” who were not directly involved in a police incident. Among teachers in the region who express support for removing students to alternative facilities, we found a mixture of frustration with the work being asked of them, deficit-oriented perspectives of students, particularly students of color, and important insights on the lack of resources or systems to support students. While the subtle racism in many of these exchanges is clear, these complicated feelings and perspectives also suggest that many teachers, especially special education teachers in the region, are struggling in the existing system, requiring both a re-examination of special education and of the racist narratives and practices that individuals perpetuate within this system.

The other major justifications for removal to alternative settings in the regions are safety and gang involvement. Even in schools that adopted restorative justice, adults explain that restorative justice was not appropriate for addressing safety or gang issues.

For example, an educator explains:

“My idea of restorative justice is, is to reintegrate the student or the teacher back into the situation. But once we’ve deemed that a student has made a situation unsafe, I don’t think it’s appropriate to try to repair relationships and bring them back into the campus. And so, I think it’s a safety issue at that point.”

Teachers explain that some students “need more of a confined school with more parameters, more boundaries, more consequences.” However, there was little examination or exploration of the roots of community violence or the conditions that spur gang affiliation in the region.8 The adults, mostly educators, who discuss “gangs” in the region evoke the idea to describe a conversation-ending external threat — the explanation for removal or exclusion that requires no additional explanation.

While we saw very little evidence of gang activity, an interview with a young person who self-identifies as a gang member in one of the schools, provides important insights that if engaged with seriously by school personnel, makes an argument for different support rather than exclusion. His thoughts on other students and his nuanced and mature assessment of different American institutions, like schools, police, and gangs, are particularly insightful.

We found little recognition or deeper thought given to gang involvement, which if understood more holistically, is often associated with prison and immigration policies, migration patterns, personal loss and trauma, and young people’s yearning for belonging and purpose. Instead, we found that the gang imagery evoked by many adults in the region justifies punishment, policing, and exclusion.9

CREATION OR RE-CREATION OF IN-SCHOOL DETENTION AND SUSPENSION ROOMS

School administrators in the region have or are in the process of creating or re-creating in-school detention and suspension rooms, primarily driven by the contradictions that arise when policy and district accountability pressure require schools to reduce suspensions, teachers demand support for classroom discipline, and alternatives are experienced as either unavailable or ineffective.

Of the 11 comprehensive schools in our sample, 7 had active in-school detention or suspension rooms euphemistically called the “Responsibility Center,” “Student Resource Center,” and “Reset Room.” In most instances, the research team observed these rooms to be places where students spend one or more class period after being sent out of class for violating dress codes, or awaiting disciplinary response or mediation. Students at times were asked to fill out a reflection sheet describing what occurred, but most often either sat alone on their phones, put their heads down, or talked with friends who were also sent to the room.

In one set of observation notes, a researcher describes:

“Some report being sent to the SRC [Student Resource Center] for misbehavior and some said they had actively chosen to come there because they found waiting around preferable to whatever was going on in class. In the back of the room student advocates are busy working one-on-one with students, trying to get through their caseload, and at the front of the room, a monitor is too busy checking students in and out to run circles or do more than joke around with students. Some students sent to the SRC seemed genuinely upset to be there, like a girl who was ‘dress-coded’ for ripped jeans and forced to waste the entire day because her mother was working and could not come to the school. Other students used the time to nap, visit with friends, or seemed pleased to be away from a teacher they particularly clashed with.”

One administrator’s description illustrates the contradictory use of these rooms for both exclusion and poorly-resourced attempts at support:

“Okay, so [our in-school suspension room] is somewhat of a… pardon me for using sort of like a jail parlance, but it’s kind of sometimes how the kids see it is like a holding tank. All right, ‘I got sent out of class, so I go to [room number] until I’m able to go to my next class.’ Fortunately we have great monitors who build relationships. So, it’s often positive and therapeutic for students there. We maybe don’t have the resources with kids in there to systematically approach from a restorative practices perspective, but our campus monitors tend to be naturally restorative.”

Adults who supervise these rooms often know students by name, explaining that they are “frequent flyers” who regularly spend time in these rooms. We observed more evidence of resource scarcity at the school site in large school districts than we did in smaller school districts, a finding we describe more fully in Section III.

Conversations with students support findings regarding in-school suspension or detention rooms. Students share a great deal about these rooms and understand them to be central to the discipline system at their schools, even when, on many occasions, administrators avoid speaking about them. In several schools, students during focus groups explain that students enjoy being sent out to these rooms and even build identities revolving around being Room X students. One student explains, “Sometimes even those kids think SRC gets fun because they don’t have to do anything. It’s like, ‘Oh let’s go to SRC.’ I’ve heard kids say that … I hear kids sometimes say, ‘I’d rather go to SRC than be at school.’”

The data suggest that these rooms persist in part, because they continue to meet the institution’s needs without requiring deeper changes. Students have an escape valve when they are fed up with classes or particular teachers, teachers can continue to remove students from their classes, and administrators have a place to hold students and make their teachers happy without much interference with their daily work.

We found that the use of these rooms was increasing, rather than decreasing in the region. For example, in one school where we found evidence of considerable district pressure to reduce suspensions, administrators had closed down a previous in-school suspension room but then created a new “program” with a different name that served much the same purpose. Administrators in this school explained that students who would have been suspended for low-level offenses in the past instead are sent to this room for the same number of days as a normal suspension but meet with a counselor to reflect on the incident and complete work.

While understandably an improvement from sending a student home with no work, students treated in this way are still excluded from class and little or no effort to re-engage students occurs after. A school administrator explains that this practice was brought to the site by a district administrator who learned of this through professional conferences and suggested that they, “Make it work for your site.” In another school, the RJ coordinator who used a room for Restorative justice circles and mediation explains that he began to also create an adjacent room for detentions as a response to teacher pressure.

In the most supportive use of a disciplinary room that we found in our school sample, a teacher trained in RJ through his educational preparation trains students to be mentors for others and creates a restorative process for students sent to the in-school suspension room for two out of the six periods of the day. In this school and during these periods, when students are sent to the in-school suspension room, students are matched with a peer mentor who listens to the student and guides them through a process of reasoning, building rapport along the way. Then the student calls over the restorative justice teacher-lead, who then takes the next step to help the student address their issue.

Another teacher in the school explains the process:

“So, if a student gets sent out of class, they usually go to in-house suspension, which is [Room]. With the exception of two periods, third and fifth period, we have a restoratives practices class. Instead of taking them to that class, they go to [Teacher’s Name] class. He has some students in there that are like mentors. They ask them what the issue was, he tries to talk to them, resolve the issue. Try to do some sort of restorative work about how to mend the issue with the teacher or whoever they had an issue with. And then, oftentimes, he’ll go over their grades, and they try to have a discussion. So, they’re attempting to do something more restorative, as opposed to punitive or isolation.”

This integration of restoration and student supports within the in-school suspension system is unique. Unfortunately, due to the loss of funding to support the program and the teacher’s release time, the program is declining at this school. Administrators admitted that for most teachers, “They don’t care, really. The bat phone is like magic to most people. You can call it and you get rid of my problem and that’s the end of it. So, they don’t really follow up whether they go to RP [restorative practices] or to in-house. ‘He’s out of my sight.’” The loss of grant funds coupled with the ease of teachers using the “bat phone,” or the direct cell phone call to administration to remove students from class (alluding to the “bat signal” in Batman), has returned this school to a more punitive approach to discipline.

USE OF ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES FOR MAINTAINING ORDERLY HALLWAYS DESPITE CHAOTIC OR INTELLECTUALLY-DEADENING CLASSROOMS

We found nearly universal adoption of Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS), Restorative justice (RJ), or both in the focal schools in the region. However, we also found that most schools in the region use these alternative approaches, particularly PBIS and the criminal justice-derived restorative justice model, to conform student behavior to dominant adult expectations rather than to create more supportive, inclusive, or empowering educational experiences for young people.

In these schools, expectations are set by adults and taught to students. If a student does not conform to these expectations they are “corrected.” For example, an administrator celebrates what he considers one of the main successes of PBIS implementation at their school largely in terms of the desires of teachers for supervision and social control in common areas:

“We do a survey, a school safety survey — a culture survey. We call it culture survey with our staff and when you look at what they feel is important it’s safety. When you ask the question about ‘What do you think is working on our campus?’, it’s PBIS. It’s supervision. We’re all out. Our counseling team and the admins are out for the most part every passing, every lunch and breaks, so we’re out there, we’re visible. We’re not in our towers with sniper rifles, but for the most part we’re out there and that’s what they like.”

As noted in earlier phases of the study, administrators frequently use prison terms in schools in this region. Here, we hear a comparison of lunch supervision to a prison yard. In other instances, “holding tanks” and “lockdowns” describe in-school suspension rooms and internet controls on computer use.

Confirming findings in an earlier phase of this study, we found through interview and observational data that in schools where PBIS appears most fully developed and institutionalized in everyday practices, student movement and behavior are strictly defined, taught, and either rewarded or corrected.

In this way, PBIS uses educative means to further social control. PBIS works seamlessly with existing systems of punishment like reprimands and in-school suspension rooms and flourishes in schools where individualized classroom pedagogy centers around students quietly sitting in rows copying or rewriting information.

Similar in some regards, schools in the region that implement criminal justice-derived models of restorative justice utilize mediation circles primarily to reach an agreement for restitution of harms against the school (e.g., vandalism, pranks, or threats), resolve conflicts between students or promote reflection and remorse in students for conflicts they had with teachers.

Administrators and educators in these schools use restorative justice to reform student behaviors and to elicit apologies, but rarely use restorative justice practices for its other purposes, like to build community, deepen understanding across difference, flatten hierarchies, provide opportunities for youth voice or leadership, provide feedback to educational systems, or raise consciousness about important social issues impacting the community. This restorative justice model also requires no changes to classroom practice. While these trends in restorative justice use are consistent with other regions of the state, we found that the criminal justice-derived models of restorative justice tend to strengthen the youth control partnerships in the region more so than other regions in the state.

Rather than strengthening the community or collective capacity to address social, political, and economic concerns, PBIS and the criminal justice-derived model of restorative justice in this region neatly fit into existing punitive systems. This pattern is consistent across schools regardless of TCE’s involvement. In contrast, we found that in three schools where the adoption of alternative approaches coincides with deeper shifts in adult practices or perspectives, the RJ practices are often led and sustained by educators who gained some expertise in RJ through university preparation. We will describe this more fully in Section III when we discuss support in the region for challenging punitive school discipline.

As a result of more control-oriented purposes for adopting PBIS and RJ, we found evidence of orderly hallways hiding sometimes chaotic and frequently intellectually-deadening classroom climate and culture. By and large, educators across the region applaud the adoption of PBIS, RJ, and the continuance of existing disciplinary practices for creating more orderly lunch and passing periods and reducing fights. The research team’s experience of the schools through multiday school visits further confirmed that the common areas in the focal comprehensive school in this region were calm, welcoming, and safe. Puzzling, however, to our team is that these calm hallways often hide from view significantly uneven classroom environments that range from safe to unsafe, and from a semblance of learning to no learning at all.

On one end of the spectrum we observed in a minority of classrooms, teachers being verbally abusive to students, students being disrespectful to teachers, and teachers no longer attempting to teach. On the opposite side of the spectrum and in an even smaller minority of classrooms, we observed scientific experimentation, lively artist studios or band rooms, and small groups of students helping one another with math.

In most classrooms in the region, however, we observed intellectually-deadening spaces. We observed uni-directional (teacher to student or computer to student) deposition and regurgitation of unquestioned facts, with little or no student engagement with one another. Particular standards governed topics (e.g., identifying different geographical formations and how they were created or the reasons for World War II) and are not contextualized or made relevant to students’ lives. Students in high school are often asked to cut and paste answers from an online book or the internet onto slides, take down notes dictated by a teacher, copy notes off a board, define vocabulary words on a computer program, or sit quietly for long periods of time to receive instructions. These patterns persist and perhaps are heightened in numerous classrooms in the region that offer one-to-one computer technology to students.

These findings are consistent with previous research findings that schools perpetuate and enact a hidden curriculum in which schools enrolling working-class students prepare students for low-wage jobs, emphasizing punctuality and following instructions, and completing boring and repetitive work without complaint. The bank-and-regurgitate model of teaching practices we observed in most classrooms are in contrast to classrooms we observed in two schools that enroll more middle and upper-middle class families. These classrooms emphasized problem-solving, group work, decision-making, self-direction, and critical thinking. In the educational spaces serving wealthier families, we found that adults allow students much more freedom of movement within classrooms and in common areas, encourage conversation among students, and utilize RJ for community building and addressing harm.

THE EXPANDED ROLE FOR ASSISTANT PRINCIPALS — AN UNEXPECTED INSTITUTIONAL IMPACT

The most significant, perhaps unintentional, institutional impact of the recent attention to school climate, culture, and discipline is the enlargement of the traditional assistant principal role, creating an important new site for either institutionalizing a more supportive and humanizing vision of school climate, culture, and discipline, or reproducing and strengthening systems of control and surveillance.

Data suggest that recording and reporting upon suspensions led to increased attention to school climate and culture and an enlargement of the traditional role of assistant principals. Rather than just responding to crises and office disciplinary referrals, assistant principals or equivalent school administrators in each of the schools in our study are responsible for practicing new approaches, creating new systems, providing professional development and training, charting progress, pursuing and managing grants, and attempting to impact classroom practice. These changes in the traditional assistant principal role are important to note because the pipeline of who can and should lead these efforts and the training and structural supports required to do this work well are potential places for either school transformation or further solidification of the youth control complex and school-prison nexus.

Back to top ↑

6. INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORTS FOR CHALLENGING PUNITIVE AND EXCLUSIONARY SCHOOL DISCIPLINE

What strategies and resources support educators in the central valley to challenge punitive and exclusionary school discipline practices? What are the remaining obstacles?

TEACHERS EXPRESS DIVERSE PERSPECTIVES ON SCHOOL DISCIPLINE

In any school change effort, teacher leadership and engagement are critical to institutionalized and sustained reform. We found that in relation to efforts to challenge and supplant punitive school discipline practices in the focal schools in this region, teachers that we observed and interviewed demonstrate a variety of responses to non-punitive school discipline reforms.

We found little evidence, if any, of teachers actively resisting positive or restorative approaches to school discipline in the region. Alternatively, only a small minority of teachers shared that participation in Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) or Restorative justice (RJ) transformed their practices along with their core values or beliefs.

Rather, we found that on matters of school discipline a vast majority of teachers expressed support for educative and/or restorative reforms to discipline. Of these, approximately half shared that their approach to students has always been educative and restorative.

In their classrooms, we observed welcoming and organized learning spaces (e.g., positively oriented posters that reflect the teacher’s own humor or interests, clear classroom norms, neatly organized materials, desks organized for group work, and student work, photos, and thank you cards on walls). We also found teacher-student interactions to be firm, familiar, and kind (e.g., “Please take out…,” “Mr. X, please put away…,” “Can someone please read…? Thank you.”). These teachers may or may not have tried out alternative approaches and were often aware of other teachers’ complaints about these approaches but did not feel strongly for or against the reforms. It is important to note that although we found these classrooms to be respectful learning spaces, the rigor and demands for independent thought remained limited, a finding we describe in Section II.

The remaining teachers in this group express support for non-punitive approaches to discipline, but voice frustration with the motivations and the resource-constrained implementation of these approaches:

“When teachers start feeling like ‘I’m asking for help, I’ve got a kid who was doing all these things,’ and they just put them right back into my classroom after talking to him for two minutes’ — that’s not working for teachers. That’s a problem. So, what are the human resources needed to make this work effectively?”

Another teacher describes:

“Now, this year, you write a referral, the vice principals will come to you, they’ll find you and ask you in person, ‘What really happened?’ It’s like, ‘I wrote it on the referral.’ A lot of teachers are not happy with that. I told you what happened, and you’re going to ask me, was it really like this? ... I put it like that. They’re [administrators are] not doing much. They’ll have a conference with them [students], and they’ll be back in class the next day. They keep changing the system. We can’t write referrals for being tardy. They want us to do a whole lot of things before we can get that. So first, we have to conference with them. Then we have to call their parents, which is fine. Then we have to have a meeting with the parent before we even write a referral to them.”

Administrators shared that most of the teachers who raised concerns were teachers that rarely had discipline issues in their classrooms:

“As far as our naysayers, our fence sitters, they were the loudest ones out there but yet they were the classrooms that never sent any students for referrals. They had their classroom management. They were solid. Then we had the two to three teachers that sent everybody, but then that told us, ‘Let’s work with you. Let’s go in your classroom. Let’s talk about classroom management. What are you doing? What routines do you have?’”

Classroom observations further confirmed that many of the loudest critics of these approaches were teachers who tended to have few, if any, major discipline issues in their classrooms. These teachers tended to have a wider range of pedagogical practices, ranging from formal teacher-centered classroom pedagogies to student-centered ones described above.

In the region, we found a positive association between those schools that adopted PBIS and stronger social control values and beliefs among administrators and educators in those schools. It’s difficult to know which preceded the other from our data, but schools with stronger social-control cultures among staff gravitate toward PBIS because of the natural congruence between PBIS’ focus on behavioral modification and educators’ prior values and beliefs in these schools. It is not surprising that social control and punishment remained in many of these schools despite the addition of some positive or rewards-based components of the PBIS model such as awards assemblies, verbal recognition of rule following, etc. Educators, at times, voiced a critique of monetizing learning or found the practice tiresome, explaining the lack of deep institutionalization of PBIS bucks.

For schools that adopted Restorative justice, we found a high degree of congruence between teacher beliefs about learning from mistakes and aspects of Restorative justice practice that were more easily accepted and practiced by teachers. Restitution, reflection, and remorse all resonated with teachers.

There is a high degree of congruence between teacher beliefs about learning from mistakes and aspects of RJ practice that were more easily accepted and practiced by teachers in schools that adopted restorative justice. Restitution, reflection, and remorse all resonated with teachers. What is more challenging for many teachers is the notion that restoration can include the need for changes in teacher or classroom practice. The underlying principles of RJ — building community, addressing and repairing injustice, challenging unequal power relations — are missing in these schools. Thus, the desire for an externally-led process to return a remorseful student to the classroom frequently resulted in frustration.

We observed a smaller subset of teachers (approximately only 5 percent of our sample) that symbolically complied with the policy to not punish, but continued practices inconsistent with the underlying values of the efforts.

We observed a smaller subset of teachers (approximately only 5% of our sample) that symbolically comply with the policy not to punish, but continue practices inconsistent with the underlying values of the efforts. These teachers do not send students to the office but were observed harshly reprimanding, berating, or ignoring students in their classrooms. These teachers share that the students are essentially being coddled and running the show. For example, in one school, teachers express that with the new rule that students cannot be suspended for disruptive behavior, coupled with the restorative practices approach that imposes no “real discipline,” teachers have no option but to endure out-of-control and disrespectful student behavior in their classrooms. Some teachers report simply keeping misbehaving students in their classrooms because “if we send them out, we are literally docked or called in.” They report that when they complain to the administration about these problems, their entreaties are rebuffed. Our observations confirm this dynamic.

INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORTS FOR CHALLENGING PUNITIVE AND EXCLUSIONARY SCHOOL DISCIPLINE

Given this distribution of teacher values, beliefs, and practices in the region, what have been or can be institutional supports for deepening efforts to challenge punitive or exclusionary school discipline?

The central relationship that determines a teacher’s response to a policy is the degree of congruence between their own ideology (or world outlook) and the policy’s demands for change in practice. For example, how similar or dissimilar are the policy values, understandings, and practices from those of the teacher? A teacher’s ideology or world outlook affects their values, beliefs, expectations of students, their job expectations, and behavior patterns. Their social position (i.e., class, race, gender, ability or disability, and other social markers) shaped these deep-seated values and beliefs. Teachers’ formative experiences, such as their upbringing, professional training, and workplace experiences, can also influence their deep-seated beliefs and values.

We saw evidence of diverse teacher ideologies regarding teaching, learning, and school culture. Consistent with teacher demographic trends nationally, the teachers we interviewed in the region are primarily white, with most teachers growing up in nearby towns, going away for college temporarily, and returning to teach. A majority of teachers we interviewed in the region did not necessarily plan on teaching while in school but fell into the position and found they liked it. We also found a growing number of Latinx teachers and administrators who grew up in the area and returned to teach. As described previously, among teachers in our study, we found both asset- and deficit-oriented narratives of students, parents, and communities; with adults holding deficit-oriented narratives comprising a minority of our sample. Among this minority of teachers expressing deficit-oriented narratives, white teachers predominate. However, deficit-oriented narratives do not necessarily correspond to more observed punitive approaches to students in the classroom or poorer instructional practice.

These patterns, which are supported by prior research, suggest that additional educator pathways that support the recruitment, preparation, credentialing, and employment of teachers from the same cultural, racial, and socio-economic backgrounds as most students in the region are important. Furthermore, these findings suggest that attention to the preparation and ongoing support for non-punitive disciplinary practices and humanizing and critical pedagogies for all teachers in the region is necessary.

We turn our attention to the existing institutional supports in the region and the remaining obstacles to suggest next steps for challenging punitive school discipline in the region.

EDUCATOR PREPARATION AND TRAINING PROGRAMS, PARTICULARLY UNIVERSITY-BASED

In the region, we found that many leaders and teachers of Restorative justice (RJ) trained through in-depth programs, often housed in undergraduate or graduate university programs.

In particular, Fresno Pacific University (FPU)supported the preparation of the school administrator or teacher practicing restorative justice in five of the seven comprehensive schools practicing RJ in the region. Some were graduates of Peacemaking and Conflict Studies or FPU’s teacher or administrative preparation program that includes an FPU-derived model of RJ, the Discipline that Restores. The central figure leading the development of RJ in another school in the region prepared in RJ through Colorado State University’s graduate programs.

The PBIS implementation in the region is primarily supported by the Fresno County Office of Education (FCOE) and Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPA) PBIS training program that relies heavily on the University of Oregon’s PBIS founders, Rob Horner and George Sugai. We found that teachers and administrators educated through these programs have strong grasps of the theory, principles, and complexities of implementation and can speak about these issues in-depth.

Several non-profit organizations provide different forms of institutional support for the region. One is Restorative justice for Oakland Youth (RJOY) that provided training and sustained networks for two of the restorative justice schools in the region. The second is the International Institute for Restorative practices, which provided training for one school. Finally, the PBIS Champion Model System is an active trainer for the region participating in FCOE training and supports and working with a number of other Central Valley districts.

While administrators and teachers generally share positive experiences of RJOY training, this is not the case for the other trainers in the region. We share more about this in the following sub-section, which focuses on obstacles.

These findings are consistent with previous research that demonstrate teacher and leadership preparation programs are critical places where teachers and principals form their professional values, schemas, and scripts about teaching and learning, suggesting an important location for strengthening institutional supports for non-punitive school disciplinary practices.

FLAT DISTRICT ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

In the region, one strength that we found in a number of school districts is a relatively flat organizational structure between the district central office and schools, allowing for much more decision-making and leadership at the school site and seemingly more school-level resources funded through district allocations.10 Seven of the nine districts in our study are small, serving between 500 and 10,000 of students.